I should briefly write about the cultural context: this is the Heian period (794-1185), one of the richest periods of Japanese culture. Japan was heavily influenced by Chinese culture, but it was during the Heian period that the Japanese were starting to shake off the influence and create their own styles and aesthetics.

At this time, men were writing in kanji (Chinese characters) whereas women were not allowed to learn it and Chinese classics, and instead, were writing in Japanese script kana (though it should be noted that both Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagon knew Chinese, but had to conceal it). In addition, men wrote poetry and some forms of prose (such as history, diary...) but not fiction, as fiction (tales) was looked down on and became a female form.

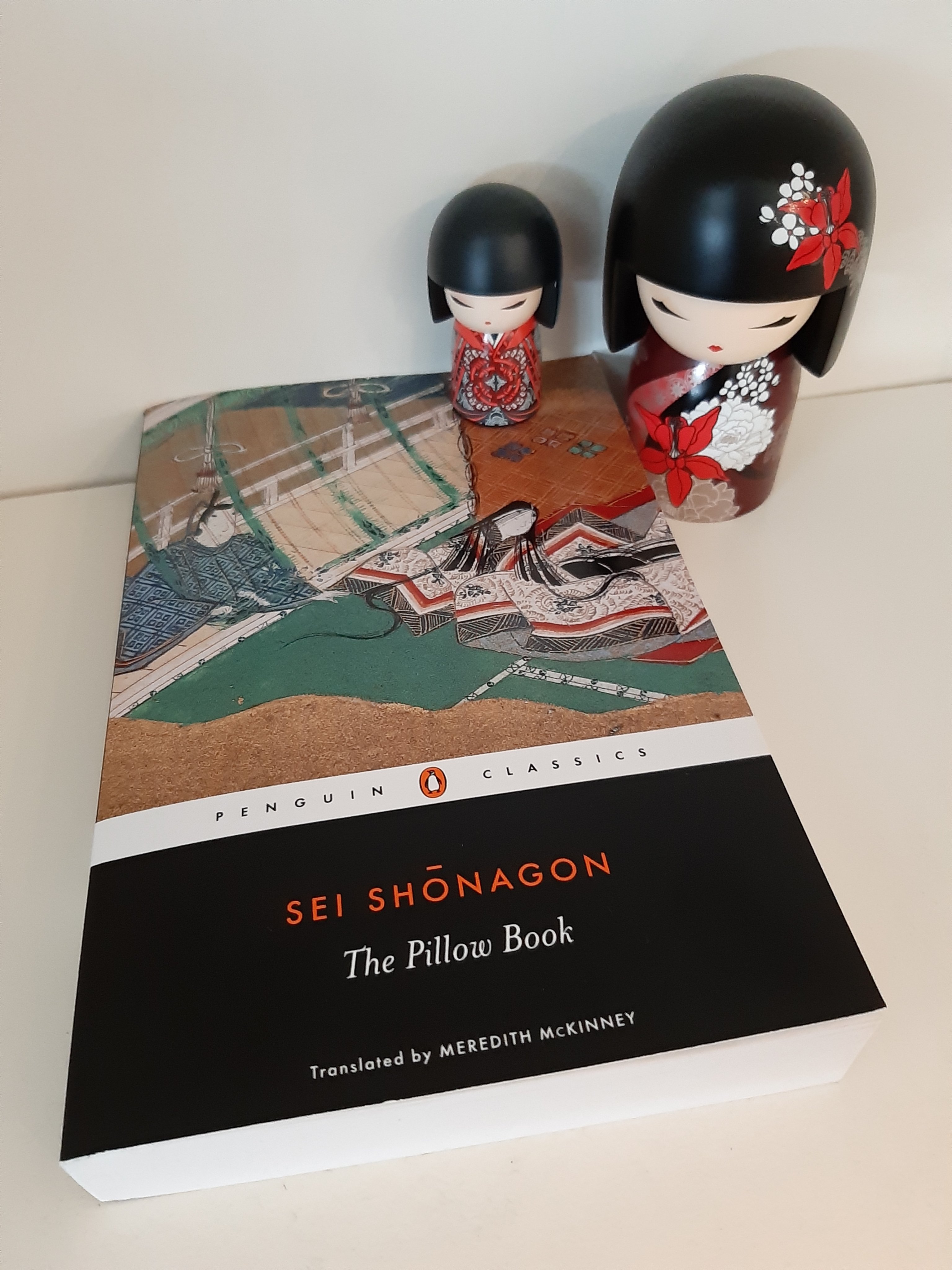

Ironically over time, it was largely women who developed a uniquely Japanese writing method and had a central role in the emergence of Japanese vernacular literature. Many of the greatest and most important works from this era were written by women, most notably The Tale of Genji and The Pillow Book. Both of them also became historical documents, depicting life at Heian court—customs, habits, festivals, values, and so on.

Sei Shonagon and Murasaki Shikibu were not only contemporary but also knew about each other—the former was serving Empress Teishi (who gradually lost backing as her father died and her brothers got disgraced and exiled), and the latter entered court to serve Empress Shoshi (who was gaining standing as she got the unprecedented appointment as a concurrent Empress to the same Emperor). It’s possible that Murasaki Shikibu was sent to court to be rival to Sei Shonagon.

2/ I don’t think it’s possible to compare The Tale of Genji and The Pillow Book, as they’re different forms—the former is a psychological novel or a long tale, and the latter is a literary genre called zuihitsu, a form consisting of loosely connected personal essays and fragmented ideas. The writings in The Pillow Book can be divided into 3 types: narratives (events and incidents she experienced at court, or fictional scenes like part of a romantic tale), thoughts on various subjects, and lists (such as “dispiriting things”, “infuriating things”, “things that make your heart beat fast”, etc).

But we can compare the authors.

The Tale of Genji, as I have written before, captures the intellectual and moral climate of the Japanese court in the Heian period, but if you read The Pillow Book right afterwards, you realise that it’s not any more Japan than War and Peace is Russia (by which I mean, War and Peace is not Russia but Tolstoy’s Russia).

In some ways, the 2 authors are similar—both are ladies-in-waiting, or gentlewomen; both are highly intelligent, observant, and knowledgeable; both know Chinese but have to conceal it; both love nature and culture; both are part of a culture of refinement and elegance. But they are very different, with different temperaments. It’s a different perspective—The Pillow Book shows the court through the eyes of a gentlewoman (The Tale of Genji has an omniscient narrator and some interesting gentlewomen but largely focuses on the nobility), and Sei Shonagon’s view of the world is different.

“Japanese critics have often distinguished the aware of Genji monogatari and the okashi of Makura no sōshi. Aware means sensitivity to the tragic implications of a moment or gesture, okashi the comic overtones of perhaps the same moment or gesture. The lover’s departure at dawn evoked many wistful passages in Genji monogatari, but in Makura no sōshi Sei Shōnagon noted with unsparing exactness the lover’s fumbling, ineffectual leave-taking and his lady’s irritation. Murasaki Shikibu’s aware can be traced through later literature—sensitivity always marked the writings of any author in the aristocratic tradition—but Sei Shōnagon’s wit belonged to the Heian court alone.” (source)Murasaki Shikibu is introspective, sensitive, and deeply aware of the fragility and uncertainty of everything, and even though she’s also funny and there are some comic scenes in The Tale of Genji, the overall tone is melancholic and darker towards the end. Sei Shonagon, in contrast, is witty, hilarious, possibly extroverted, sometimes arrogant, snobbish, even mean, and she often sees the amusing or absurd side of things. My impression from The Pillow Book is that she has a strong personality, laughs a lot, and can be confrontational and intimidating.

I’ve just read about the solemn exorcist monks, or the wistful partings in The Tale of Genji, then I’ve got to The Pillow Book—everything appears absurd.

3/ Sei Shonagon isn’t interested in soul-searching. The Pillow Book is basically about her personal likes and dislikes, her opinions on things, and the things she finds delightful about the world in which she lives. It’s not only a valuable historical document but also interesting for itself—the reason The Pillow Book is still read and still enjoyable is that the author has a strong personality and appears very vivid, very real on the page. She is fascinating.

In the introduction, Meredith McKinney discusses different speculations about Sei Shonagon’s intentions for writing The Pillow Book. It may be personal, but there’s an awareness and acknowledgement of an audience, and the book seems like an equivalent of the modern day’s blog. The lists may be her personal views, but they may also be a catalogue of shared tastes and opinions. But whatever the intentions are, Sei Shonagon comes to epitomise the sensibility of Teishi’s court.

Like The Tale of Genji, part of the charm of The Pillow Book is the alien, sometimes strange environment and culture depicted, and part of it is that you recognise the things she’s talking about, and go “yes! I can relate”. She speaks directly to me from 1000 years ago. The culture, customs, and social norms may be different, but human beings haven’t changed at all.

4/ I once saw someone complain about the lack of political intrigue in The Pillow Book. Indeed, the translator Meredith McKinney provides the background, and lots of things were happening when Sei Shonagon was at court—Empress Teishi’s position became insecure as her father died, power went to his brother/rival, then her brothers became exiled, and the rival established his daughter Shoshi as an Empress. These things only get a brief mention, if at all, in The Pillow Book, and don’t get discussed in detail.

I too would be curious about her thoughts, but this condescending complaint seems to me quite ignorant. One must remember that Sei Shonagon’s writing non-fiction, about real people and real events, so she cannot go far as far as Murasaki Shikibu can in The Tale of Genji—Murasaki also moves the settings of her novel to the 10th century, probably so that others don’t think she’s writing about current conflicts at court. Sei Shonagon’s also not part of the nobility—she’s at court to serve an Empress and can be kicked out or punished any moment if she offends someone of high rank. Even though she means to write for herself, other people are aware of her writings.

5/ Compared to Murasaki Shikibu (and some other writers I love), Sei Shonagon is very worldly, entertainingly so. She’s interested in things, scenes, and people. She writes anecdotes and character sketches, and describes events at court. That’s part of the appeal.

She’s also not very religious, compared to Murasaki Shikibu. As written above, exorcist monks, so solemn and holy in The Tale of Genji, are portrayed in The Pillow Book as amusingly ineffectual, exhausted, drowsy, and desperate not to become laughingstocks. Or, she may describe her pilgrimage to the temple at Kiyomizu and start off writing about the reverence, but she soon gets distracted.

“If it’s at New Year, though, the place is simply an uproar of noisy activity. You have no hope of pursuing your own practice, you’re too busy watching the endless melee of people to the temple to offer up prayers for this and that.” (entry 115)And then:

“You always wonder who it is if you don’t recognize them, and it’s fun to try to identify the ones you think you do recognize.” (ibid.)She’s too interested in people.

But then, why should I be surprised? After all, early on in the book, she says that preachers should be good-looking because, if we are to absorb what he’s saying, we must keep our eyes on him as he speaks.

Personally I’m not religious, and I may dislike certain things about organised religion. But I do love the supernatural elements in The Tale of Genji, especially the spirit of the Rokujo Haven, which is strange and one of the finest creations I’ve encountered in literature. As Royall Tyler has noted in his book of essays about the novel, the way the Rokujo Haven isn’t aware of any hostility towards Aoi but her jealousy and bitterness takes the form of a spirit to attack Aoi savagely shows Murasaki Shikibu’s awareness of a gap between conscious and unconscious feelings. That is brilliant.

6/ The greatness of The Tale of Genji is more obvious to see, and easier to talk about—we can talk about the great scope, characterisation and psychological insights, techniques, style, beauty, descriptions, structure, themes, ideas, moral vision, and so on.

It is harder to talk about the brilliance of The Pillow Book. In a way, Sei Shonagon does appear superficial because of her interest in things and scenes (and some of her narratives may count as gossip about people at court), and sometimes she does sound conceited, as Murasaki Shikibu remarks in her diary. But she’s very clever, quick-witted, and extremely funny, and she can convey well the various scenes and life in general at court—the Heian court appears vivid, intimate, and full of life under her pen. She’s also sensitive to beauty.

Mostly the charm of the book is the author herself, and I can’t help feeling drawn to her. Sure, she often sounds mean and definitely snobbish, but I relate to her because she apparently has a short temper and tends to be confrontational. As she describes in the book, a few times a close male friend and she may have some argument over something minor and she gets a bit confrontational, but she doesn’t really bother and the friendship ends. She is flamboyantly alive on the pages, we see her flaws, but she still appears charming but I can’t help feeling drawn to her.

A simplistic way of explaining the different ways I feel about the authors is that Murasaki Shikibu is a genius I put on a pedestal, and I see Sei Shonagon as a friend.

This shouldn’t be taken lightly—is it not remarkable that I feel a connection with a woman living in Japan over a millennium ago?

Here is a thread of things I find fascinating in The Pillow Book (still to be updated).

No comments:

Post a Comment

Be not afraid, gentle readers! Share your thoughts!

(Make sure to save your text before hitting publish, in case your comment gets buried in the attic, never to be seen again).