1/ One may ask why Royall Tyler, as a translator, doesn’t pick a nickname for each character and stick to it, to make it easier for modern readers. This is his explanation about the social world of The Tale of Genji, and his decision to retain the way the narrator refers to the characters:

“This feature of the original text has been retained to preserve the character and structure of the social world that the narrator brings to life. The fictional narrator speaks from within this structure, and for her, good manners require conventional discretion. As a gentlewoman to a great lady, she of course stands high in the overall population of her time, counting from peasants up, but peasants and so on do not belong to her world. Hers is that of the court, in which she has a modest place. Her language must acknowledge this place, and it must also convey the way her characters would think and talk about each other if they were real.

To put it another way, the absence of personal names from the narration is another distancing device that screens a lord or lady’s person from the outsider’s gaze. […] The way the narrator refers to people affirms less their individuality than their position in a complex of communally acknowledged relations that was of absorbing interest to all. To give the characters invariant designations (in effect, personal names) would therefore be to shift the narrator’s courtly stance toward a modern egalitarian one.”

2/ The baffling contradiction is that this social world has a strict hierarchy, but there are no real lines when it comes to sex and affairs.

What I mean is that, in today’s world, there are certain lines—most people wouldn’t have sex with their first cousins, their best friend’s partner, or children. The world of The Tale of Genji doesn’t have such “rules”.

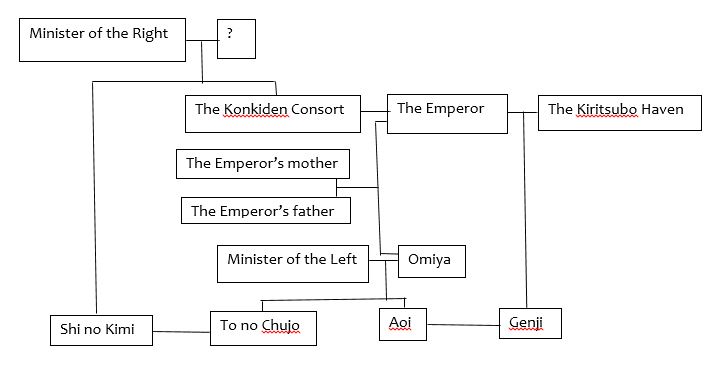

If we look at Genji, he’s married to his first cousin (Aoi), and so far he has been involved with a married woman of lower rank (Utsusemi, the cicada woman), her stepdaughter—whom he stumbles upon whilst looking for Utsusemi (Nobika no Ogi, the reed woman), an older widow (the Rokujo Haven, the jealous woman), his close friend’s ex (Yugao, the twilight beauty, To no Chujo’s ex), an ugly and boring woman that he thinks has nothing to offer (Suetsumuhana, the red-nosed woman), his stepmother (Fujitsubo), her little niece (Murasaki), a staff woman of about 57-58 (Gen no Naishi), and his other stepmother’s sister (Oborozukiyo, the moon-at-dawn woman, sister of the Kokiden Consort). So much incest.

(A note: the Kokiden Consort is the Emperor’s wife before he marries the Kiritsubo Haven and has Genji. Their son Suzaku is the Heir Apparent, who in chapter 9 becomes the new Emperor. After the Kiritsubo Haven’s death in chapter 1, the Emperor marries Fujitsubo).

Is there anyone that Genji leaves alone?

But it’s not just him. Genji’s close friend To no Chujo chases the old staff woman when knowing that Genji is doing so. In this society it’s apparently not a thing to stay away from your close friend’s lover.

This world is messed up in other ways. For example, in chapter 8, Genji is involved with Oborozukiyo, who is intended for the Heir Apparent—i.e. her nephew. I mean, what? Is there no sense of order at all?

Keeping track of these characters is difficult enough, and requires full immersion in the novel, but Murasaki Shikibu makes them distinct and memorable. It is keeping track of relationships—seeing how characters relate to each other—that is difficult.

I have just realised, for example, that Genji and To no Chujo relate to each other in another way. We know that Genji is married to To no Chujo’s sister Aoi (their father is the Minister of the Left), so they are brothers-in-law. They are also cousins, because Genji is the Emperor’s son, whilst To no Chujo’s mother is Omiya, the Emperor’s sister.

At the same time, To no Chujo is married to a daughter (Shi no Kimi) of the Minister of the Right, and the Minister of the Right is father of the Konkiden Consort, so To no Chujo’s father-in-law is Genji’s stepmother’s father.

See the family tree I drew.

In other words, To no Chujo is Genji’s brother-in-law, but also Genji’s stepmother’s father’s son-in-law.

What did I just write?

3/ Genji screws almost everyone at court, but in a discreet way, and he fears for his reputation. He often goes out in disguise, keeps Murasaki a secret, and needs others to cover up for him, such as Koremitsu’s handling of the Yugao situation or To no Chujo’s silence about his affairs. The Emperor doesn’t know about his flirtations and numerous affairs, and most people at court have an image of him very unlike his true character. Murasaki Shikibu, in a subtle way, contrasts the way Genji is seen by people not close to him, especially the Emperor, and the way he really is. She therefore makes the readers re-examine and see the irony in other people’s perception of Genji as wonderful and perfect.

Genji is definitely portrayed as imperfect, but he’s not all bad either—he does care about his women instead of playing with their feelings and throwing them away. He has sensitivity and compassion, and tries not to hurt the feelings of the women he has slept with, even if he doesn’t care about them anymore, such as the reed woman or the red-nosed woman.

In chapter 9, it upsets Genji when he hears about the skirmish between Aoi’s people and the Rokujo Haven’s people. He just wants the women to have peace, and nobody to get hurt. Later, when his first wife Aoi becomes pregnant and unwell, he understands his duty to her, but comes to tell the Rokujo Haven to make her understand and not feel neglected. Does he need to do so? Not really, but he chooses to, anyway, the same way he chooses to send expensive presents to the red-nosed woman and her gentlewomen.

In chapter 4, and then chapter 9, we can see that Genji has depth of feeling, and sincerely cares for the women in his life.

4/ One would ask, what about jealousy? Genji has so many women, there must be some jealousy.

So far, the image of jealousy in The Tale of Genji is in the character of the Rokujo Haven. However, she is different from Hoạn Thư (Lady Hoan) in Nguyễn Du’s Truyện Kiều, who becomes an archetype in Vietnamese culture.

Hoạn Thư’s jealousy is the possessiveness, anger, and malice of a first wife—she has more legitimacy and power, and looks down on the other woman (Kiều). In a similar positon in The Tale of Genji would be the Kokiden Consort, but she cannot compare to Hoạn Thư in cleverness and maliciousness, at least so far.

The Rokujo Haven’s jealousy is the jealousy, misery, pain, humiliation, and bitterness of a lover—a neglected, helpless lover. As herself, she is helpless and does not dare to claim anything, but her jealous rage takes the form of a spirit to fatally attack other women, even while she’s alive.

This is something I’ve never seen in a novel before, but it works so well in The Tale of Genji that it not only doesn’t appear at all out of place, but it also leads to such evocative images and powerful moments in the novel, especially in chapter 9.

Why did Virginia Woolf, in her review of Volume I (Waley’s translation), think the novel lacked force?

5/ To those unfamiliar with the story, I should note that Genji’s relationship with Murasaki is not based on paedophilia—he doesn’t have a particular interest in children, Genji is no Humbert Humbert. His attraction to her is because of her resemblance to Fujitsubo, his stepmother and her aunt, and his relationship with her is rooted in the idea of teaching and moulding her into a perfect wife.

Genji sees Murasaki for the first time when she’s 10, and brings her home, but doesn’t have sexual relationship with her until chapter 9—when she’s about 14-15. In today’s understanding, she’s still a child, and most readers wouldn’t help feeling grossed out, but this is 11th century Japan.

As I have said before, because this world is so alien and operates by such different rules that it’s hard to evaluate Genji’s actions and know Murasaki Shikibu’s thoughts about her characters and their world. However, we can see that other characters are shocked by his interest in the girl and disapprove of his abduction, and he himself has to keep it a secret for several years.

We can also see that their first sexual experience is unexpected, shocking, and unpleasant to the girl, and that Genji doesn’t understand it.

Valerie Henitiuk wrote an essay, comparing 3 translations, imagining a Genji translated by Virginia Woolf, and raising the question of male vs female translators: https://twitter.com/nguyenhdi/status/1267902864690642951

In it, she does write about the differences between the original and the translations regarding the scene with Murasaki in chapter 9.

The book, meanwhile, is getting better and better.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Be not afraid, gentle readers! Share your thoughts!

(Make sure to save your text before hitting publish, in case your comment gets buried in the attic, never to be seen again).