1/ In The Tale of Genji, usually each chapter follows the previous one without break or there may be a break of a few months.

Then in chapter 35, something unusual happens. All of a sudden in the middle of a chapter, there’s a jump of 4 years. The count is Royall Tyler’s, but it’s based on the mention of Reizei’s age in the same sentence.

Then comes another change in reign, which means that everyone again changes titles:

- Reizei abdicates because of health problems and becomes His Eminence. He is son of Fujitsubo and Genji, though to the public he’s son of Fujitsubo and the Kiritsubo Emperor (the first Emperor in the novel).

- Suzaku, the previous Emperor, has earlier renounced the world and become a monk, so he is His Cloistered Eminence.

- His wife the Shokyoden Consort, who died within that 4-year gap, is posthumously appointed to the highest rank.

- The Heir Apparent becomes the new Emperor—the 4th Emperor in the story. He is son of Suzaku and the Shokyoden Consort. He doesn’t have a nickname, as far as I know.

- His eldest son with Genji’s daughter becomes the new Heir Apparent. They also have a daughter (the First Princess) and in this chapter she is pregnant with their third child.

- Higekuro: previously the Right Commander, becomes the Left Commander, and then Minister of the Right. He is brother of the late Shokyoden Consort. His first wife is daughter of the Lord of Ceremonial (Murasaki’s half-sister), his second wife is Tamakazura (Mistress of Staff, Yugao’s daughter).

- Yugiri: the Right Commander, becomes Grand Counsellor. He is son of Genji and Aoi.

There are other promotions as well, but these are the important ones.

The thing worth noting is that the Retired Emperor Reizei doesn’t have descendants of his own. The new Heir Apparent is Genji’s direct descendant but it is through his daughter, which isn’t the same, and the Reizei line, which in itself is a disruption of hierarchy, is cut off.

2/ To recap, so far there have been 4 Emperors in the book:

- The Kiritsubo Emperor: Genji’s father.

- Suzaku: Genji’s half-brother.

- Reizei: Genji’s son, but his half-brother in name.

- The new one: Genji’s son-in-law.

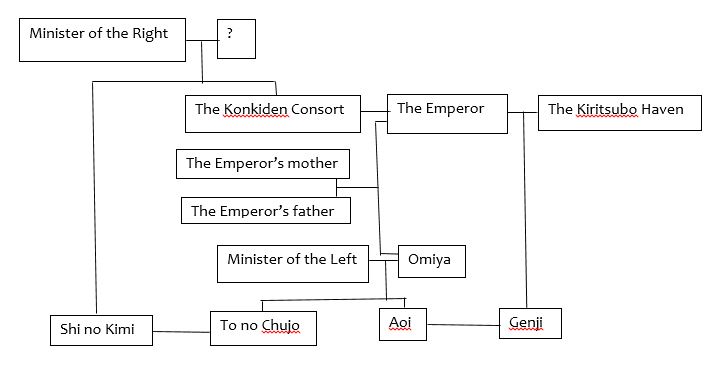

I should draw a family tree for illustration but their inter-connections are too complicated.

3/ His Highness of War (Hotaru) marries Higekuro’s daughter with his first wife.

As I have a morbid obsession with how the characters relate to each other, let’s see: His Highness of War is Genji’s half-brother, and Higekuro’s first wife is Murasaki’s half-sister, so His Highness of War marries his half-brother’s wife’s half-sister’s daughter.

If we look at their relationships another way, he is also Suzaku’s half-brother and Higekuro is the late Shokyoden Consort’s brother, so His Highness of War marries his half-brother’s brother-in-law’s daughter.

Are you confused?

4/ The Tale of Genji is a Buddhist novel. The gods and buddhas are mentioned frequently, the characters talk about karma and reincarnation and the vanity of things, they go on pilgrimage, etc.

The thing I don’t quite understand is why many characters in the story just renounce the world and become monks or nuns, or at least talk about doing it.

In a few cases, a woman becomes a nun to keep herself from being harassed by men and save her name from getting tainted, like Utsusemi (cicada), or to protect herself, partly living in quiet and avoiding court politics, and partly seeking salvation, like Fujitsubo (Genji’s late stepmother). As Royall Tyler explains, in this society a woman only has one refuge outside a stable relationship with a man: becoming a nun. In both of these cases, they don’t go into the mountains (like the Akashi Novice) or join a monastery—they take religious vows, cut their hair short, wear plain, discreet colours, and stay at home. This is a radical step that is not to be taken lightly.

In Genji’s case, he wants peace and quiet—he learns the vanity of all things after the many deaths in his life, and especially after the exile, realises that life is treacherous, so he plans to renounce the world after seeing his children well-settled.

There are other monks and nuns in the story, such as Akashi’s father and mother, Murasaki’s great-uncle, the monk who knows about Fujitsubo’s secret, and so on.

But why does Suzaku (the second Emperor in the novel) become a monk? What about Asagao (bluebell) and Oborozukiyo?

And why does Murasaki speak of leaving the world? I reckon Murasaki knows that her life is forever insecure, and wants to go away before getting abandoned by Genji. Religion is a woman’s only refuge.

5/ Throughout the novel, we see Murasaki’s jealousy and resentment a few times and get an idea of her feelings about her relationship with Genji, but it is in chapter 35 that we truly know how she feels.

She has been lucky, she thinks, getting more favours than (she thinks) she deserves, but it is forever an insecure life because of her dependence on Genji and his feelings. The 2 women who have caused her most insecurities are Akashi and the Third Princess (Onna San no Miya, Suzaku’s daughter).

She has resented Akashi in the past, partly because of Akashi’s elegance and accomplishments according to Genji and partly because they have a child together. She has been afraid of the Third Princess, who is superior to everyone else in rank and moves into the main house, and people think the Princess should be placed above all of Genji’s women—it’s just fortunate that she is childish and bland. But Murasaki’s whole life is insecure—when she’s young, the bond with Genji may not be so strong and there are numerous other women; when the bond becomes stronger over time, she’s aging and younger women have the advantage of youth and freshness.

The Tale of Genji places a male character in the centre, but in many ways it is about the female characters, about a woman’s fate in the Heian period of Japan.

6/ Chapter 35 is a great chapter (so is 34).

The Tale of Genji is brilliant from the start and gets better and better, then a few chapters become less intense, but it picks up again around chapter 34 and becomes particularly intense and haunting with the return of the vengeful spirit. The book may be called psychological realism with some supernatural elements, but the supernatural elements fit in so perfectly that there seems to be nothing unnatural or abnormal about them.

Is there anywhere else a more fascinating depiction of a woman’s wrath?

7/ There is not a smooth transition but a sudden cut from Murasaki’s illness to Kashiwagi’s (To no Chujo’s eldest son) affair with the Third Princess, which I don’t particularly like.

But afterwards the story is interesting again, and the narrative moves nicely between Murasaki and the Third Princess.

Apart from predatory men, a lady at court has another “enemy”: her own gentlewoman. As it turns out, Suzaku’s concern is not unfounded and Genji’s fear is correct—the Third Princess indeed has no sense. As Genji thinks to himself, the trouble with her has never happened to his women—especially not the proper ones such as Murasaki and Akashi. His “guidance” cannot prevent her from being foolish and committing an error, and Kashiwagi is insolent.

But at the same time, can Genji say he’s any better? He has betrayed both Suzaku and his own father.

8/ Kashiwagi is an asshole though, one must say. He has been fantasising about the Third Princess but couldn’t get her and therefore marries her sister the Second Princess (like Kim Trọng loses Thúy Kiều and marries Thúy Vân in The Tale of Kieu), but cannot get over his crush. See what he writes down:

“O wreath of twinned green, what possessed me to pick up just the fallen leaf,

though in name it seemed to be as welcome as the other?”

He refers to his wife as a fallen leaf!

(It’s because of this poem that the Second Princess comes to be called by readers as Ochiba, “fallen leaf”).

Then afterwards when Genji finds out his shameful secret, he blames the Third Princess for being careless and letting him get a glimpse of her!

9/ The scene of Genji and Kashiwagi at the dance is interesting. In front of others, Genji has to pretend to treat him normally and know nothing about the fling, Kashiwagi knows that he’s pretending but he himself has to pretend that he doesn’t know.

1/ There must be many moments in The Tale of Genji when the modern reader, non-Japanese especially, feels that something eludes them.

When reading chapter 17 “The Picture Contest”, I couldn’t help feeling that I didn’t fully comprehend what Murasaki Shikibu was describing and talking about—Royall Tyler’s very helpful in explaining the different styles, colours, and references, but my lack of knowledge about Japanese arts was a barrier to understand fully what was happening and what was the meaning and significance of the paintings and the debates.

Now in chapter 32, “The Plum Tree Branch”, all the descriptions of incense-making/ incense-judging and calligraphy are beautiful and fascinating, and I get the main points, but part of the meaning still eludes me because I know absolutely nothing about incense and calligraphy. When Murasaki Shikibu writes about handwriting and the writer’s character throughout a book, I understand it, because I still write by hand regularly (and judge people’s handwriting). But when she goes deeper and writes about men’s style vs women’s style, etc. it’s beyond me.

2/ The way Murasaki Shikibu handles the friendship between Genji and To no Chujo is particularly good. In their youth they’re best friends though there’s a bit of rivalry going on. Then as they get older, the rivalry becomes more serious as both try to gain more power at court and have different plans for their children, and they drift apart, especially after To no Chujo separates his daughter Kumoi no Kari and Genji’s son Yugiri. But then Tamakazura (Yugao’s daughter) brings them close again, and afterwards To no Chujo accepts the marriage between their children.

It is a very good scene when To no Chujo and Genji talk about Tamakazura and recall their memories together, then Genji thinks about it but chooses not to bring up the subject of Yugiri and Kumoi no Kari, whilst To no Chujo thinks he’s ready to approve of the union and waits for Genji to speak but sees that he doesn’t. They keep misunderstanding each other.

Interestingly, the narrator ponders about the rivalry between Aoi and the Rokujo Haven when they’re alive and when they’re dead. Aoi’s son Yugiri is still a commoner, though he has a good position and high regard at court, whereas the Rokujo Haven’s daughter is now the Empress.

3/ Koremitsu’s daughter, earlier known as a Gosechi dancer, is now the Fujiwara Dame of Staff. She and Yugiri have had a fling.

To confuse matters, in chapters 34, there are 2 Mistresses of Staff:

- Oborozukiyo: sixth daughter of the former Minister of the Right and sister of the Empress Mother (Kokiden Consort at the beginning of the book). She is one of Suzaku’s women (the second Emperor), and the one tangled in the scandal that causes Genji’s banishment. She still can’t resist Genji (naturally).

- Tamakazura: Yugao’s daughter, now wife of Higekuro (the Right Commander). They now have 2 children together.

4/ In these chapters, Murasaki goes from being called the lady of the southeast quarter or the lady of spring, to the lady of Genji’s east wing.

In chapter 33, “New Wisteria Leaves”, we see the start of friendship between Murasaki and Akashi, as Genji’s daughter enters the palace and is “returned” to her mother. Earlier Murasaki has been jealous of Akashi, but they like and respect each other—each can see why Genji holds the other in high esteem, and apart from the love of Genji, they share a daughter.

Personally I like them both. Murasaki is described as elegant, accomplished, loving, and patient—her only perceived flaw is that she doesn’t bear Genji a child. She understands Genji better than anybody and sees through him, but he sometimes fails to understand her because he can sometimes be thoughtless and she’s too proud and conscious of people’s talks to express bitterness or jealousy, though sometimes she can’t help it. She accepts his affairs (and deceit) in quiet suffering.

Akashi is Genji’s 2nd favourite among his women—she’s also my 2nd favourite. As I have written before, her personality is interesting because she’s proud and shy at the same time, and fully aware of a woman’s place in this society—at first she hesitates to accept him and only acquiesces because of her father, then she hesitates about moving to court and only chooses to settle at Oi, and only joins Genji when he moves to the Rokujo estate, away from court. Somehow I imagine that the author would be closer to Akashi than Murasaki.

In a way, the friendship between Murasaki and Akashi might seem strange, because they share a husband (see the wives’ rivalry and hatred in Raise the Red Lantern), but there is no bitterness between them and ultimately the thing that binds them together is the daughter they share and both love. On Murasaki’s side, she has the kindness and sensitivity to understand Akashi’s loneliness and sacrifice—Akashi never puts herself forward and tries to claim anything. On Akashi’s side, she can’t help liking the kind and loving woman who has done a lot more for her daughter than she has dared to hope.

Out of Genji’s women, the one least developed so far is Hanachirusato (falling flowers, northeast quarter). I don’t see her as clearly as I see Murasaki and Akashi and many other characters.

5/ Suzaku (the second Emperor in the novel) has 5 children:

- The Heir Apparent: the mother is the Shokyoden Consort. Genji sends his daughter to palace to become his Consort—she then becomes the new Kiritsubo Consort.

- The Third Princess (Onna San no Miya): his favourite among the 4 daughters.

Earlier when To no Chujo was manoeuvring his daughters into “the right places”, I was thinking that he treated his daughters like chess pieces and didn’t care about their feelings. But the situation with a Retired Emperor’s daughter is different, and Suzaku’s concern for his daughter makes me see everything in a new light: in this world a woman needs the protection, guidance, and backing of a powerful patronage, or she might stray and dishonour herself and lose her social standing. Suzaku cannot comfortably leave the world until he has found his daughter secure, that’s why he has to place her in Genji’s protection, making it impossible for him to reject becoming her husband/ father/ guardian.

Am I ruining it when noting that Suzaku and Genji are half-brothers, which makes Genji her uncle?

In a sense The Third Princess disrupts the entire ranking when she moves to the Rokujo estate. She is a princess whereas all of Genji’s women are commoners—in terms of rank, she is higher than anyone else. Luckily she is bland, disappointingly bland in Genji’s eyes, and still a child. She cannot compare to any of his women (except Suetsumuhana perhaps).

Kashiwagi, To no Chujo’s eldest son, is interested in her however. In chapter 34, his title is Intendant of the Right Gate Watch. I expect an affair between them.

According to Royall Tyler’s notes, he’s in his mid-20s, whereas the princess is her mid-teens.

6/ See these lines about Yugiri and Kumoi no Kari:

“His wife had no great merit or any particular wit, despite his deep affection for her. Familiarity had dulled his enthusiasm now that all was settled between them, and at heart he still found it hard to turn his thoughts from the varied charms of the ladies his father had brought together—especially Her Highness, of course, since, considering her birth, his father showed no sign of any great interest in her, and he could tell that his father was only keeping up appearances. Not that he had anything untoward in mind, but he did not want to miss any chance to see her.” (Ch.34)

Is that not a bad sign? Yugiri is already bored with his wife, and interested in his father’s women.

7/ In chapter 34, the Kiritsubo Consort (daughter of Genji and Akashi) gives birth.

I’m going to be a spoilsport by noting that the birth takes place sometime after Genji’s 40th birthday celebrations—according to Royall Tyler’s calculations, she’s about 12 then, and the father, The Heir Apparent, is about 14.

1/ In chapter 28, “The Typhoon”, we can see that Yugiri is becoming more and more like his father.

2/ How many men at court pursue Tamakazura (Yugao’s daughter)?

- Genji: her guardian.

- Yugiri: Genji’s son with Aoi.

- To no Chujo’s sons, i.e. her half-brothers. These people need to calm down with all the incest.

- His Highness of War: previously Prince Hotaru. He is Genji’s half-brother, but I’m not sure who the mother is. Genji encourages Tamakazura to accept him but she doesn’t.

- Higekuro: the Right Commander. His nickname means black beard. He is brother of the Shokyoden Consort (who is married to Suzaku, the second Emperor in the novel, and mother of the current Heir Apparent). His wife is daughter of the Lord of Ceremonial (previously His Highness of War) and Murasaki’s half-sister.

- The Intendant of the Left Watch: Murasaki’s half-brother. He’s not mentioned till chapter 30, “Thoroughwort Flowers”.

- Reizei, the current Emperor.

Did I miss anyone?

The only man that seems to interest Tamakazura is Reizei and she goes along with Genji’s suggestion to become the new Mistress of Staff, which would make her serve the Emperor as a quasi-wife but not give her an official title. But she ends up marrying Higekuro.

I had a discussion on Twitter with Knulp and Marina about the marriage, and we compared translations: Tyler’s, Seidensticker’s, Washburn’s, and the French one: https://twitter.com/nguyenhdi/status/1274305190590656513

There seem to be some significant differences. I wasn’t sure about why Tamakazura accepted Higekuro when there was no development, but according to Wikipedia, he rapes her, which is possible, judging by the hints in Tyler’s translation. It makes sense and all the reactions fit together. In that context it’s more accurate to translate that afterwards Tamakazura is unhappy than to write that she finds everything tedious.

3/ The Tale of Genji is very subtle and indirect, and Murasaki Shikibu sometimes throws out details in a way that is unusual to the modern reader and easily missed.

For example, between chapter 29 and chapter 30, Yugiri (Genji’s son) is promoted from the Captain to the Consultant Captain. She doesn’t say anything about the change. Right when the character appears in chapter 30, she calls him the Consultant Captain without an explanation.

However a few lines later, she has a reference to him seeing Tamakazura’s face the morning after the storm (chapter 28), so we know it’s him.

Similarly, their grandmother (Omiya, mother of Aoi and To no Chujo) dies between chapters—Murasaki Shikibu doesn’t mention her death, she starts chapter 30 by describing Tamakazura’s grey clothing (which we know is the colour for mourning), then moves on to describe Yugiri’s mourning clothes. Then they talk and allude to the fact that Tamakazura doesn’t want outsiders to know that she’s in mourning because at this time only a handful of people know she’s To no Chujo’s daughter.

Everything is very subtle and indirect.

Murasaki Shikibu also introduces characters in “unconventional” ways (but who came before her?). For example, Higekuro has been appearing for many chapters, known as the Right Commander, but only in chapter 30 is he introduced as being related to so-and-so.

This is why Royall Tyler’s translation is extremely helpful, because at the beginning of each chapter he has a character list, and within the chapter itself he adds lots of notes and helps readers remember the characters. This version is very reader-friendly, without spelling everything out and ruining the text.

4/ It is surprising to see how passive, almost indifferent To no Chujo is, after knowing about Tamakazura and Genji’s plans for her.

He is unkind to Omi no Kimi though. She is his newly discovered daughter and may have countrified manners, not wholly suitable for court, but he always makes fun of her, usually without her knowing. Genji may also be unkind to the red-nosed woman sometimes, but not in front of her.

Omi no Kimi is interesting however. Murasaki Shikibu may describe her as rustic and lacking in taste (especially in the letters) but also gives her charm, some kind of innocence, and a liveliness that makes everyone else appear stiff and affected next to her.

5/ In these chapters we have other male characters to whom to compare Genji.

Chapter 31 focuses on Higekuro, who is more of a douchebag. He rapes his new wife, and wants to throw away his first wife, who seems to have some mental illness. The Tale of Genji is written in the 11th century and apparently set in the 10th century, so naturally people have no understanding of mental illnesses and think she’s attacked by some spirit and get monks to “exorcise” her.

However, I think it’s clear that Murasaki Shikibu has sympathy for her—for both of his wives. Higekuro is indifferent to both women’s feelings and only cares about himself. He is also possessive.

He takes her away from the palace and moves her directly to his house, instead of letting her go back to the Rokujo estate, and thus breaking protocol. However, as To no Chujo makes no objections, there is nothing Genji and Tamakazura can do. Genji’s plan is thwarted. But at the same time Genji becomes much better—much nicer, in comparison.

6/ What I find even more interesting is the reaction from the Lord of Ceremonial. He decides to move his daughter (Higekuro’s first wife) back to his house to protect her, but several years earlier, when Genji’s stripped of his rank and title, he cuts off all ties with Murasaki—also his daughter. Of course the situations are different and this one needs him more than Murasaki does, but is it not appalling that he protects one daughter but abandons another to protect himself?

7/ As the Lord of Ceremonial takes his daughter away, he also takes his granddaughter and doesn’t give Higekuro access to her.

Look at this line:

“In her youthful innocence she suffered acutely from everyone’s merciless condemnation of her father and from the mounting insistence on keeping her away from him.”

Is that not something that we can recognise today? Different cultures may have different beliefs and practices, norms may differ, society may change over time, but certain things about human behaviour remain the same.

8/ I’m not a Freudian, but I can’t help thinking about resemblance and the idea of substitution in The Tale of Genji.

Tamakazura looks like her mother Yugao. Reizei looks like his father Genji.

I’m going to get it out of the way by saying that Moby Dick doesn’t fit into this way of dividing big novels, because Moby Dick is more than a novel—it is 3 books put together (a novel, a whale encyclopaedia, and a philosophical book), and the story is only a small part of the book.

Some recent articles and posts about big novels have made me think about them and storytelling, and I’ve come to the conclusion that big novels can be roughly divided into 2 types.

The 1st type is the multiple-strand novel, which is essentially several novels put together. An example is Anna Karenina, in which we have the Anna strand and the Levin strand. Some characters belong to both sets of characters, such as Kitty or Oblonsky, but the Anna plot and the Levin plot are separate.

Middlemarch is similar, which has 3 main plots: Dorothea- Casaubon, Lydgate- Rosamond, and Fred-Mary. Again, they sometimes intersect, but each of these plots can function as a novel on its own, even though the Fred-Mary one is thinner in comparison. Daniel Deronda is a better example, in which the Gwendolen Harleth plot and the Daniel Deronda plot only touch.

Little Dorrit is less clear, but once I wrote that there were 4 strands of story in it: the Marshalsea prison, the Clennams, the bureaucrats, and the Marseilles prisoners. The line is more blurred, compared to Anna Karenina or Daniel Deronda, and Arthur Clennam connects all 4 plots, but they are separate—the world of the Clennams is distinct from the world of the Marshalsea prisoners and the Dorrit family, for instance, and the plot of the Marseilles prisoners is the one that stands out the most.

Now look at War and Peace, it is different. It is the 2nd type, the one-big-story novel. War and Peace has 5 families and about 500-600 characters—they are all inter-connected and their lives are intertwined. Some readers speak of the War part and the Peace part, but they are just separate by location and action—they are not separate in the sense that they could be different books put together, especially if we look at characters such as Andrei and Nikolai. Andrei and Nikolai are not points of intersection of different strands the way Arthur Clennam is in Little Dorrit—their lives unfold in both the War part and the Peace part.

A better example is The Tale of Genji, which is longer than War and Peace but tells a single story of Genji with his women and children. I’ve been told that about 2/3 or 3/4 through the book, Genji would die and the author would move on to tell the story of his children, but that would be a continuation. The entire book tells a single story—there are about 400 characters in the book but most of them relate to Genji one way or another. At least till he dies, Genji is always the central character, even if Murasaki Shikibu switches between perspectives.

I think the 2nd type is harder to write. With the 1st type, you’re essentially writing 2 or several novels at the same time—you have to move back and forth between the plots, but generally speaking you’re focusing on one set of characters at a time. In contrast, when you write the one-big-story novel, the characters are not divided into different sets and you have to juggle with everyone at the same time. In The Tale of Genji for instance, Murasaki Shikibu must have full control over her 400 characters—what they’re doing, where they’re living, how old they are, when they move from one residence to another or how they move from serving one person to another, and so on. She has to keep track of passing time, age, seasons, festivals, amount of mourning time after a loved one dies, etc. and has to keep track of everyone’s age and changing titles as well as their relationships with each other.

There may be some works that are hard to categorise, but I think big novels can be roughly divided into these 2 types.

What do you think?

1/ I’m going to go straight to the point by saying that Genji is such a dick sometimes.

In the previous blog post, I was probably creating the impression that Genji wasn’t too bad, as he matured over time and changed after his exile. But Genji doesn’t become a different man. Murasaki Shikibu, in a skilful way, drops little hints here and there that even though he seems to settle down and builds a new house for his women, he’s not quite content with them. There’s a part in him that can’t resist pursuing other women.

For many chapters, he still pursues Asagao (bluebell), for instance, even though she always resists him.

Murasaki Shikibu sets it up so that, when the thing with Tamakazura (Yugao’s daughter) happens, it is abhorrent but not a surprise. He brings her home, and for several months acts a guardian and talks about fatherly feelings, but afterwards wants to sleep with her.

Just look at what happens with the Ise Consort earlier (daughter of the late Rokujo Haven, formerly Priestess of Ise, and now the Empress). The only reason Genji doesn’t get involved with her is because her mother, in her deathbed, has asked him not to. Even then, he betrays himself at one point. That animal in him doesn’t go away.

The thing with Tamakazura is only the next step, and the author shows his shamelessness in “courting” her whilst talking about fatherly feelings.

Murasaki Shikibu is, for the large part, invisible in the text and the narrator usually appears only to remind us that she is a gentlewoman telling the story to an audience (her superiors)—only rarely does she comment on something. But her feelings about Genji’s odious behaviour to Tamakazura are quite clear—the narrator briefly comments on his strange way of being a father, but mostly we can see it in Tamakazura’s reactions (disgust, anger, pain) and Genji’s callousness.

“That is the way of the world”, so Genji says (ch.24).

2/ There are some similarities between Murasaki and Tamakazura in their situations.

In both cases, Genji keeps them away from their biological fathers and acts as a father/ guardian, and then forces himself on them.

In both cases, they are a substitute for someone else—Murasaki resembles her aunt Fujitsubo (who in turn looks like Genji’s dead mother), whereas Tamakazura looks like her mother Yugao.

Imagine Freud reading The Tale of Genji.

A crucial difference between the two is that Murasaki is about 10 when Genji first sees her and abducts her, whereas Tamakazura is about 21 when he brings her home.

3/ How many children does To no Chujo (Genji’s brother-in-law) have? In a note at the end of chapter 25, Royall Tyler says:

“As far as one can tell, 10 sons and 4 daughters.”

I don’t know about you, but I sure am glad that it’s the tale of Genji, not the tale of To no Chujo.

To be quite honest, I’m at a loss about who’s who among his sons, because each time one is mentioned, my eyes just glaze over the title, “right, one of the sons, whatever”. In chapter 26, Royall Tyler helpfully lists the children as they appear in the chapter:

- Kashiwagi: the Right Captain, his eldest son. In these chapters, he unknowingly pursues Tamakazura. In chapter 27, he becomes the Secretary Captain.

- Kobai: the Controller Lieutenant, his 2nd son.

- The Fujiwara Adviser: his 3rd son.

- Kokiden no Nyogo: his eldest daughter, the Consort. In earlier chapters, he introduces her to the Emperor (Reizei, Fujitsubo’s son), but he favours the Ise Consort and picks her to be Empress instead. To no Chujo is bitter about this failure.

- Kumoi no Kari: his daughter with another woman (who is married to Inspector Grand Counsellor). Genji’s son Yugiri loves her but To no Chujo separates them because he has other ambitions for her.

- Tamakazura: his daughter with Yugao. Known as the pink (nadeshiko), which is the same flower as gillyflower (tokonatsu), but tokonatsu refers to Yugao whereas nadeshiko refers to their child. Genji “adopts” her.

- Omi no Kimi: his newly discovered daughter. She is said to be rustic and have low-class manners and language. People laugh at her and To no Chujo is embarrassed of her.

4/ In these chapters, especially chapter 26 “The Pink”, we can clearly see what it feels like to be a woman in the Heian era of Japan—women are dependent on men and controlled by men, their lives are dictated by men. If To no Chujo uses his daughters like chess pieces to gain power for himself and his family, with no regard for their feelings, Genji appoints himself as Tamakazura’s guardian, keeps her under his control, and decides what to do with her—her thoughts are of no importance.

Tamakazura is helpless. She is in an awkward position. At the same time, the gossip about Omi no Kimi, To no Chujo’s newly discovered daughter, makes her think it may be a better idea after all to stay with Genji.

5/ In chapter 25 “The Fireflies”, there is a defence of tales, or fiction.

In The Tale of Genji, Murasaki Shikibu writes about other arts: poetry (over 800 poems in the book), music (koto, biwa, shō…), dance, painting (especially in chapter 17 “The Picture Contest”), gardening (see the way Genji designs his gardens according to seasons for his Rokujo estate), writing of tales, etc.

As Tolstoy does with Russia, in War and Peace and Anna Karenina, Murasaki Shikibu, in The Tale of Genji, depicts Japan or at least Japanese court in the Heian era—she captures the entire world with its customs and habits, the culture, the aesthetics, the thoughts.

However I should get back to this point once I’ve finished reading the entire book.

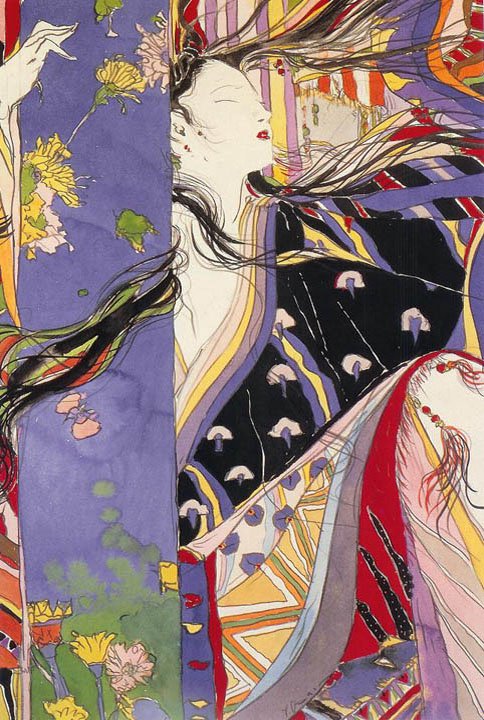

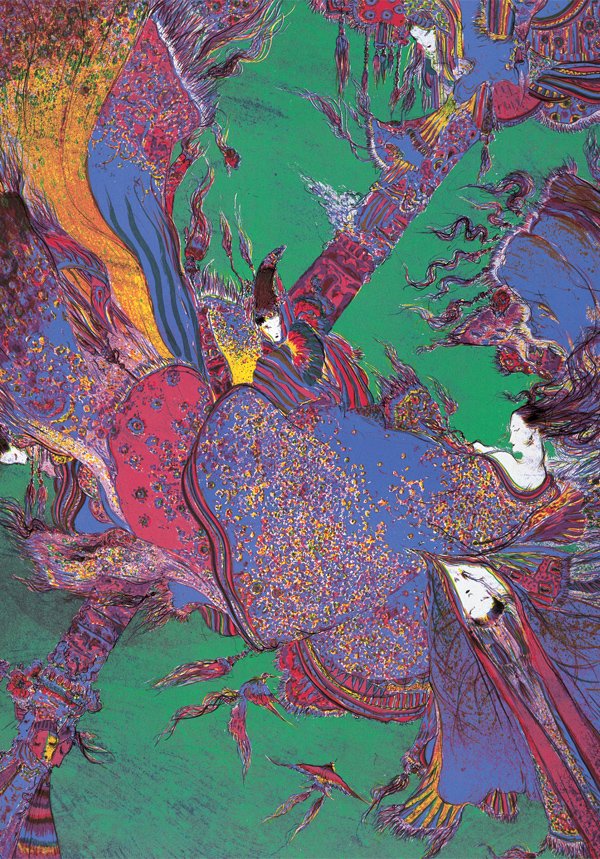

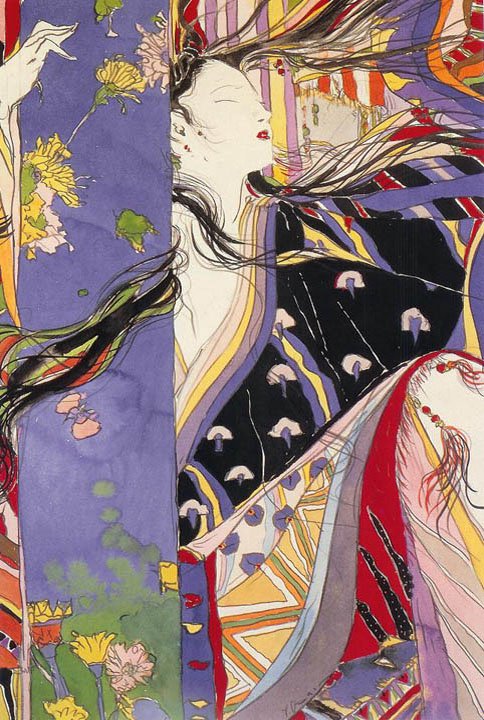

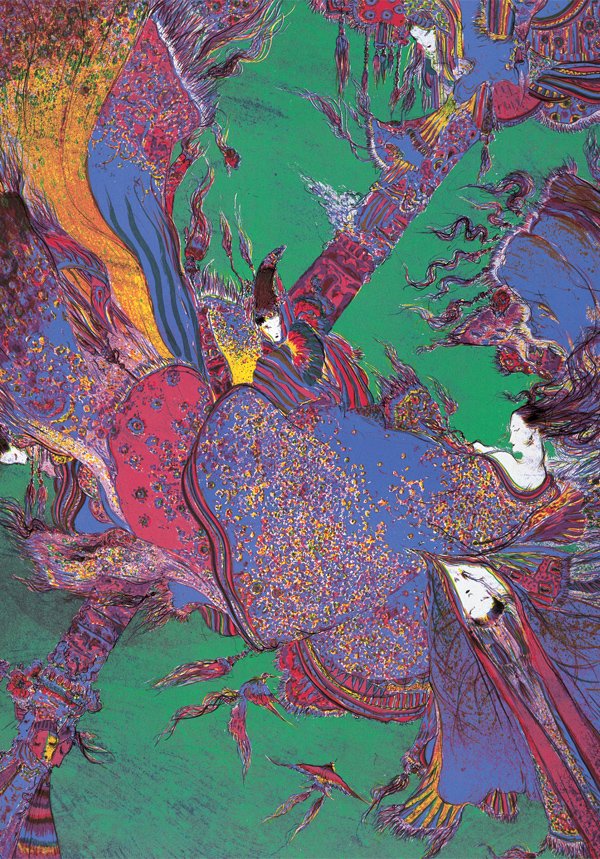

Some of Yoshitaka Amano’s paintings for The Tale of Genji.

1/ From chapter 21, titled “The Maidens”, the story starts to focus on the new generation.

Genji has 3 children, in this order:

- Reizei: Genji’s son with Fujitsubo (Her Late Eminence), but to the world, he’s son of the late Kiritsubo Emperor (Genji’s father). Currently the Emperor.

- Yugiri: son of Aoi, Genji’s first wife. Aoi dies a short time after childbirth.

- The daughter, known as Akashi no Himegimi: Genji’s daughter with the Akashi Novice’s daughter, but she’s now raised by Murasaki.

Genji doesn’t have any children with Murasaki, the love of his life.

Chapter 21 is particularly interesting for the subject of education, and also shows the difference between Genji and his best friend To no Chujo, who has several children from different women.

Genji focuses on raising his children properly—he deliberately makes it difficult for his son Yugiri by promoting him to a lower rank than expected (6th rank instead of 4th rank) and making him work for it. Genji prioritises learning and good qualities for his children. He is not that different from rich and successful parents in modern day who don’t give their children a high position or the entire inheritance but make them work hard to prove themselves.

To no Chujo, in contrast, focuses more on ambitions. Among his children, the most notable at the moment are two daughters. One of them he has introduced to the Emperor—she is now the new Kokiden Consort, but Reizei, the Emperor, prefers the Ise Consort and makes her the Empress.

Having failed, he has ambitious plans for another daughter, known as Kumoi no Kari. Her mother (not the same as the Kokiden Consort’s) is married to the Inspector Grand Counsellor. The man treats his daughters like chess pieces. The plans aren’t going well, though, because the poor girl is interested in Yugiri.

2/ In chapter 21, Murasaki Shikibu raises the question of love vs social ambitions.

Reading The Tale of Genji as a woman, I can’t help seeing how shitty it was to be a woman in that time, even for ladies at court, who were literally at the top of society. Imagine being at the bottom.

3/ In these chapters, Genji and To no Chujo are rivals, and it is interesting that very early on in the novel, Murasaki Shikibu already sets up their rivalry—see the Aging Dame of Staff.

She sets things up so cleverly that, as I recently realised, some characters were “sneakily” introduced several chapters before they officially appeared, that their introductions were not noticed by a first-time reader.

4/ Yugiri, like his father and perhaps other men at court in general, is interested in 2 girls at the same time: To no Chujo’s daughter Kumoi no Kari, and a Gosechi dancer, daughter of Koremitsu (Genji’s confidant).

I’m going to be a spoilsport by pointing out, in case it wasn’t clear, that he and Kumoi no Kari are first cousins.

5/ As Murasaki Shikibu is a cruel writer who likes challenging and torturing her readers, Genji, after building some residences nearby, decides to build another house at Rokujo estate and moves there, away from court. Again, his women change “names”.

- Murasaki: Genji’s wife (after Aoi). Fujitsubo’s niece and daughter of the former His Highness of War, now Lord of Ceremonial. Resembles Fujitsubo. Previously referred to as the lady of Genji’s west wing or Genji’s darling. Associated with the colour purple. Genji and Murasaki live at the southeast quarter—associated with spring.

- Hanachirusato: sister of the former Reikeiden Consort. Associated with the village of falling flowers. Previously the lady in east pavilion. She now lives in the northeast quarter—associated with summer.

- The former Ise Consort, the Empress (Akikonomu): daughter of the late Rokujo Haven. I’m not sure why she moves here (what about the Emperor?), but she has the southwest quarter, which is where she once lived—associated with autumn.

- The Akashi Novice’s daughter (Akashi no Kimi): Genji meets her while in exile. She and Genji are second cousins, as his late mother is daughter of the Akashi Novice’s uncle. They have a daughter together, known as Akashi no Himegini. Previously known as the lady at Oi, now often called Akashi. She now moves to the estate and lives in the northwest quarter—associated with winter.

- Suetsumuhana: also called the red-nosed woman. The late Hitachi Prince’s daughter. Associated with the safflower because of its dye. In chapter 17, Genji moves her to the west wing of the east pavilion (Genji’s Nijo estate, at court). She doesn’t move to Rokujo estate.

6/ Following the chapter “The Maidens” is a chapter about another maiden—chapter 22, “Tamakazura”, translated as “The Tendril Wreath”.

Tamakazura is the nickname for the lost daughter of Yugao (twilight beauty) with To no Chujo.

In the chapter, Murasaki Shikibu leaves the current narrative to pick up a thread from earlier.

The nurse has been bringing up Tamakazura, without knowing anything about Yugao’s fate, but after her husband’s death, has to choose between accepting a suitor for Tamakazura and going to the city to help her find her father. The interesting part is the disagreement between her and Ukon, formerly Yugao’s gentlewoman and now Murasaki’s. The nurse wants to contact the father—To no Chujo. Ukon wants to inform Genji, because she herself works in Genji’s house.

Previously, there have been conflicts between the two because Ukon has to keep the secret about Yugao and Genji, whilst the nurse doesn’t tell her about the child. Now they disagree about what to do about Tamakazura.

Finally Genji wins, and the young woman moves in with Hanachirusato (the lady from the village of falling flowers).

But isn’t that wrong? His reasoning is that To no Chujo has lots of children to busy himself with already, and he himself has only 3, but who is he to decide? She is To no Chujo’s daughter—he deserves to know.

7/ I like that Genji is (usually) honest to Murasaki. He often downplays his feelings for other women, sometimes even dismisses them as unimportant, but generally still tells her about other women, about what he plans to do or who he intends to meet, etc.

In chapter 22, he tells her about Yugao, almost without restraint.

Yugao’s daughter Tamakazura is now known as the lady in the west wing, because she lives in the west wing of the northeast quarter (sharing a building with Hanachirusato).

8/ Genji tries to make it fair to everyone.

The women are not equal—Murasaki lives in the same building with him, the other women don’t, and he doesn’t move Suetsumuhana to the Rokujo estate. But he makes sure that all of them are taken care of and get everything they need, and sometimes visits them so they don’t feel neglected, even if, in the case of Suetsumuhana, he no longer cares about her.

The case of Suetsumuhana is particularly interesting, because Genji doesn’t feel attracted to her anymore and sometimes may even be unkind to her in his thoughts or behind her back. But he feels a duty to take care of her, which he does, despite getting nothing out of it, and he still visits her, as we see in chapter 23.

Suetsumuhana, under a lesser writer’s pen, might easily have become mere comic relief, or a two-dimensional character created only to prove a point about Genji’s goodness. But Murasaki Shikibu is a great writer, and in chapter 15 gives the character more complexity. Suetsumuhana is proud, stubborn, antiquated, and not very self-aware. She is an interesting character on her own.

1/ As Genji rises in court, he builds places for his women nearby. Naturally their references change.

- Murasaki: Genji’s wife (after Aoi). Fujitsubo’s niece and daughter of His Highness of War. Resembles Fujitsubo. Often referred to as the lady of Genji’s west wing or Genji’s darling. Associated with the colour violet.

- Hanachirusato: sister of the former Reikeiden Consort. Associated with the village of falling flowers. She is now called the lady in east pavilion.

- The Akashi Novice’s daughter (Akashi no Kimi): Genji meets her while in exile. She and Genji are second cousins, as his late mother is daughter of the Akashi Novice’s uncle. They have a daughter together, known as Akashi no Himegini. She is now known as the lady at Oi.

- Suetsumuhana: also called the red-nosed woman. The Hitachi Prince’s daughter. Associated with the safflower because of its dye. If I understood correctly, in chapter 17, Genji moved her to somewhere near him, but I’m not sure what it’s called.

[Update on 14/6: Suetsumuhana, in chapter 21, is called the lady in the west wing of the east pavilion.]

The storyline about the Akashi Novice’s daughter is particularly interesting, because she’s not a complete outsider (she and Genji are related, and she is not a peasant, say), but she’s also not from court. Her father used to have relatively high rank but renounced the world and moved to Akashi, so she has been growing up in a seaside town. On the one hand, she is accomplished, and in many ways not inferior to ladies at court. On the other hand, she is not equal to many of them in terms of rank.

The Tale of Genji depicts a world in which a woman’s fate is determined by rank, specifically her father’s rank, and women must be dependent on men. As Royall Tyler explains in the introduction, Suetsumuhana is a princess because she’s the daughter of the Hitachi Prince, but Aoi isn’t a princess though her mother is one (the Emperor’s sister) because Aoi’s father (the Minister of the Left) is a commoner. He goes on to say:

“The personally daunting Aoi is of very high standing, and her father is exceptionally powerful. Her weight in her world is incomparably greater than that of the pathetic Suetsumuhana, whose father is in any case dead. Nevertheless, Suetsumuhana carries an aura of imperial quality that has not come down to Aoi.”

To go back to the Akashi Novice’s daughter, imagine that she never met Genji—she has been brought up to be much higher and more accomplished than the men she may meet in the area, but unfortunately far away from men of high rank. That is why, before meeting Genji, she thought that she would either throw herself into the sea or become a nun. That is also why she resists him at the beginning, for fear of getting hurt. The scenes at the beginning of their relationship are very good.

When Genji wants his women to move into buildings nearby, she refuses, because of pride and fear. She only moves closer, to Oi—nearer to him, but still away from court. That is her way of protecting herself, and also her way of keeping herself in Genji’s high esteem, as she’s showing that she has self-respect and makes her own choice.

However, the situation is different when their daughter starts to grow, and she is forced to give her up to live with Genji and Murasaki, because that’s for the best.

Chapter 18 and the beginning of chapter 19 are particularly moving. This is an entirely different time, an alien culture, but Murasaki Shikibu lets us see that human beings have always been the same—the mother’s feelings are all recognisable.

2/ In the little conflicts between Genji and Murasaki when he goes to other women, does the author disapprove of him for ignoring her signs of displeasure and making light of her feelings, or does she portray Murasaki as unreasonably jealous, despite knowing that other women cannot compare to her in rank and importance, and Genji is noble for being fair to all his women?

The case is probably both—Murasaki Shikibu doesn’t have to, and probably doesn’t, side with anybody. She lets us see that Genji does try to take care of all his women and is honest to her about what he’s doing, before words reach her from others. She shows us the suffering of women when forgotten by men. But she also lets us see that Murasaki can’t help feeling the way she feels, and he sometimes dishonestly dismisses other women as unimportant just to reassure her, or gets up to leave her in unhappiness instead of trying to resolve the problem between them.

Chapter 19 is great, because Murasaki, as she takes care of Genji’s daughter, empathises with the suffering and loneliness of the lady at Oi, and no longer holds any grudge against her.

3/ In Vietnamese people often say: theo tình tình phớt, phớt tình tình theo.

It probably comes from the French saying: Suis l'amour, l'amour fuit, fuis l'amour, l'amour suit.

It’s easy to tell what kinds of women attract Genji.

Older, Genji still chases after Asagao (daughter of His Late Highness of Ceremonial, associated with bluebells) in chapter 20—the more she resists, the more he chases her.

4/ There are many deaths in The Tale of Genji—3 in chapter 19.

Before, I have always seen Tolstoy as the best writer about dying and death, but Murasaki Shikibu also handles the subject in a very moving and haunting way that I can’t quite explain. Someone else would be better at expressing it than I am, but Murasaki Shikibu and Tolstoy write about death in a way that I don’t remember seeing anywhere else in literature.

She also makes me think about things differently, and makes me want to spend more time with nature.

1/ Reading The Tale of Genji, I always feel an aesthetic joy—or as Nabokov has put it, a tingle in the spine. The style is beautiful, even if I read it in translation.

But once in a while, there is a particularly magnificent chapter, like chapter 15, “A Waste of Weeds”. Look at this passage:

“In the eleventh month the weather turned to snow and sleet that sometimes melted elsewhere, but the Hitachi residence, buried in weeds that blocked the morning and afternoon sun, remained as deep in snow as White Mountain younger in Etchu, until not even servants were seen abroad, and the mistress of the place languished in vacant apathy. She had no one even to comfort her with a light remark or to divert her with tears or laughter, and at night, in the grubby confines of her curtained bed, she tasted all the misery of sleeping alone.”

Suetsumuhana, the red-nosed woman, has been waiting for Genji for years in her ruined house. Her servants, one by one, start to leave her. Nobody pays her a visit. Is it not such a striking image? She pines away in a house buried in weeds that block the sun.

Then one day Genji passes by, on the way to someone else.

“The last night rain was falling after several wet days, and the moon came out at the perfect moment. His journey to her long ago returned to mind, and he was dwelling in memory on all of that deliciously moonlight night when he passed a shapeless ruin of a dwelling set amid a veritable forest of trees.

Rich clusters of wisteria blossoms billowed in the moonlight from a giant pine, their poignant, wind-borne fragrance filling all the air around him. It did so well for the scent of orange blossoms that he leaned out and saw a weeping willow’s copious fronds trailing unhindered across a collapsed earthen wall.”

(trans. Royall Tyler)

Murasaki Shikibu’s writing is sensuous.

Chapter 15 makes us feel deeply for Suetsumuhana, and for the fate of women in Heian Japan. Left behind by her late father, forgotten by Genji, and abandoned by her own servants, she is helpless and suffers alone in a ruined house. For many chapters, she slips out of narrative, then reappears. By my calculation, she’s been waiting for about 10 years.

The interesting part is that Murasaki Shikibu doesn’t write her as a simpleton or a caricature of a lonely helpless woman—Suetsumuhana is a complex character, with the pride of someone of high rank (her father is the Hitachi Prince) and a stubborn refusal to sell things in the house, which nobody understands. She is poor and pitiful, but unreasonably proud in her behaviour toward her aunt (the Dazaifu Deputy’s wife, previously only a Governor). The character is multi-faceted.

Chapter 15 also lets us see that Genji has sensitivity and compassion—he is imperfect, and a lot of his behaviour is abominable, but he tries to help all the women in his life. Indeed, for years he has forgotten Suetsumuhana, especially with troubles of his own, but does he have to help her now? Not really. He gains nothing from it. But he does it anyway.

2/ As we follow Genji’s life, he matures and changes over time, but his outlook on life also becomes darker. Especially after the banishment, he realises that life is treacherous—people yield to pressures and betray themselves, to protect their social standing.

Genji may not reproach anyone, from his half-brother the Emperor, to the brother of Utsusemi (cicada), but he remembers it.

It is noteworthy that the only person who comes to visit him in exile is his best friend To no Chujo (Aoi’s brother).

3/ The hardest thing about The Tale of Genji is, as expected, the change of titles and positions. However, it is not as difficult as it seems, as the title changes usually happen together, rarely individually—they change because of a promotion day, or because of a change in reign.

The key thing is to keep a diagram of changing titles (apart from family trees).

- For example, when the story begins, we have an Emperor, Genji’s father. One of his wives is the Kokiden Consort, daughter of the Minister of the Right. Their child is the Heir Apparent, known as Suzaku. After Genji’s mother’s death, the Emperor marries the Fujitsubo Consort.

- After a while, the Emperor appoints Fujitsubo as Empress.

- Then the Emperor abdicates and there is a first change in reign. He becomes His Eminence. The Heir Apparent, Genji’s half-brother, becomes the New Emperor. Consequently the Kokiden Consort becomes Empress Mother. Fujitsubo’s child, known as Reizei, becomes the new Heir Apparent.

To confuse matters, the Empress Mother moves from Kokiden residence to Umetsubo residence, whereas the Minister of the Right’s sixth daughter (her sister) becomes Mistress of the Wardrobe then Mistress of Staff, then becomes one of the Emperor’s wives and moves to Kokiden residence.

- For fear of her own safety, Fujitsubo becomes a nun, and her title changes to Her Cloistered Eminence.

- A few chapters ago, there is a second change in reign: the Emperor (Genji’s half-brother) abdicates because of health problems. He goes from His Majesty to His Eminence. Fujitsubo’s child, known as Reizei, becomes the new Emperor, at the age of about 11. Fujitsubo as a nun cannot go up in rank, so she continues being Her Cloistered Eminence. The Retired Emperor has a child with the Shokyoden Consort, the Shokyoden Prince, who becomes the new Heir Apparent.

- As I wrote in the previous blog post, different factions at court introduce girls to the new Emperor. So the new Emperor (Fujitsubo’s son), still as child, already has two girls at the moment. The first one, a year older than him, is daughter of To no Chujo (Aoi’s brother, Genji’s brother-in-law)—she becomes the new Kokiden Consort.

The second one is the Ise Consort. She is daughter of the Rokujo Haven (Genji’s jealous woman—now dead) and formerly High Priestess of Ise. She is older than the new Emperor.

To those who haven’t read The Tale of Genji, these things sound very complex and confusing, but as long as you make your own notes and have a firm grasp of the characters’ relationships with each other, it’s fine. Each time it’s a chain of events—when there is a new Emperor, the roles of people around him change.

1/ Anyone who reads The Tale of Genji must sometimes wonder: but what does Murasaki Shikibu think? How does she really feel about Genji and his actions? Above all, what does she think about the patriarchal system she’s depicting?

The novel is about the women in Genji’s life as much as it’s about him. Murasaki Shikibu seems to have sympathy for them all—from Fujitsubo, who lives in anguish because of fear and guilt and has to renounce life for her own safety, to Yugao, who goes into hiding because of threats from To no Chujo’s wife; from the Rokujo Haven, who feels neglected by Genji, humiliated by his wife, and tormented by her own jealousy, to the Reikeiden Consort, who isn’t among the Emperor’s favourites when he’s alive and forgotten after his death; from Suetsumuhana, who is paralysed with shyness because she has neither looks nor wit, to the Akashi Novice’s daughter, who is painfully conscious of her low rank and doesn’t want to be involved with Genji for fear of getting hurt; from the old staff woman, who still has sexual desire and cries about the treachery of time, to Murasaki, who is abducted as a small child then abandoned by her own father, and has nobody but Genji, etc.

The Tale of Genji is so rich, so full of humanity, with a wide range of characters, especially female characters, and the author seems to love them all. The culture and social rules are alien, but the feelings are all recognisable—Murasaki Shikibu writes about love, loss, betrayal, jealousy, loneliness, grief, fear, guilt, shame, and so on.

I do not know, at least for now, her feelings about the patriarchal system of Heian Japan, but her novel does depict a world in which women have confined roles, unable to do much and hidden away behind curtains and screens, whilst each men can have several wives and lovers, and can give other women night visits. Murasaki Shikibu writes about women yielding, or running away, or getting raped (in suggestive, subtle ways); she also writes about women suffering in loneliness and waiting for a man who never comes.

2/ In chapter 10, Genji’s enemy (former Kokiden Consort, now Empress Mother) says she would cause his downfall.

In chapter 11, there’s a little break, as Genji visits the Reikeiden Consort and her sister (Hanachirusato).

But when we get to chapter 12, the downfall has happened. Murasaki Shikibu earlier has written at length about rituals, festivals, and death, but she chooses not to write about the events that led up to Genji’s banishment.

I can’t help asking, what does she think? Indeed Genji is later restored to court, but does it necessarily mean that she sides with love, so to speak, and agrees with Genji that he is blameless and unjustly treated? Or does she think that the punishment is excessive and motivated by grudge, but Genji isn’t entirely blameless either and women have always been his main weakness?

3/ See this quote from Virginia Woolf:

“Here was a woman about the year 1800 writing without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching. That was how Shakespeare wrote, I thought, looking at Antony and Cleopatra; and when people compare Shakespeare and Jane Austen, they may mean that the minds of both had consumed all impediments; and for that reason we do not know Jane Austen and we do not know Shakespeare, and for that reason Jane Austen pervades every word that she wrote, and so does Shakespeare.”

Let me change a bit:

Here was a woman about the year 1000 writing without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching. That was how Shakespeare wrote, I thought, looking at Antony and Cleopatra; and when people compare Shakespeare and Murasaki Shikibu, they may mean that the minds of both had consumed all impediments; and for that reason we do not know Murasaki and we do not know Shakespeare, and for that reason Murasaki pervades every word that she wrote, and so does Shakespeare.

That is perhaps the only thing Murasaki Shikibu and Jane Austen have in common—they both write from a woman’s perspective, and thus write about conditions for women, without letting anger, resentment, or any preaching get in the way and distort their art. They become elusive.

(Murasaki Shikibu has been called the medieval or Japanese Jane Austen—I myself have never understood these comparisons).

4/ Speaking of Shakespeare, chapter 13 has such a Shakespearean moment. Did you expect it? I didn’t. It’s not exactly the same, but it made me think of King Lear.

Powerful, intense, evocative images.

The Tale of Genji, like Moby Dick or Tolstoy, makes most novels appear small and insignificant.

5/ We are told that Genji loves Murasaki more than anyone else—the characters too believe so. He moulds her into his ideal woman, and she turns out to be as he has wanted.

Murasaki Shikibu doesn’t openly condemn the relationship, but she drops a few hints here and there. At the beginning, other characters are shocked by Genji’s interest in the girl, and he can get away with the abduction only because he’s the Emperor’s son. It is very subtle, but the scenes of Murasaki playing with dolls and not understanding his hints set a clear contrast between Murasaki as seen by Genji (a potential wife and surrogate for Fujitsubo) and Murasaki as she is (an innocent child who likes playing with dolls).

Murasaki Shikibu also lets us see the girl’s unusual and vulnerable situation—Genji becomes her mother and father, she has nobody but him, and when he is banished, her biological father abandons her for fear of consequences.

There are 2 scenes showing that their relationship (and marriage) isn’t as happy as it seems. The first time is in chapter 9, when Genji takes her virginity, unexpectedly.

The second time is in chapter 14, when he tells her about his affair with the Akashi Novice’s daughter when he’s in exile, and his plan to bring the Akashi woman and their daughter to court. He talks like it’s only a fling and he has no choice.

Both times, Murasaki is upset, angry, and hurt. Both times, she feels duped—betrayed. Both times, Genji fails to understand her feelings.

In a subtle, natural way, Murasaki Shikibu conveys that a man’s plan to shape a girl from a young age into his ideal woman cannot work—he cannot see her for who she is, and does not understand her.

6/ The Tale of Genji gives us a picture of the lives of women at the Heian court.

Women have to share a husband (think of the Chinese film Raise the Red Lantern or the Vietnamese poem Cung oán ngâm khúc—Lament of a Royal Concubine), but they are not all equal. The Emperor’s Wife could be the Empress, or a Consort (Fujitsubo comes after the Kokiden Consort but is elevated to the rank of Empress), or lower (the second Emperor in the novel, Genji’s half-brother, doesn’t appoint Oborozukiyo as a Consort, which is a shame).

A woman, in a way, has to compete to be recognised—to be one of the man’s women (Genji and the Rokujo Haven, for instance, aren’t official), and then has to compete to be a favourite, because the ones that aren’t favourites may be forgotten (such as the Reikeiden Consort). But even then, sometimes it’s not enough to be a favourite, because there are other factors—at the beginning of the novel, the Emperor’s favourite is the Kiritsubo Consort, Genji’s mother, but there is nothing he can do for her and Genji because she lacks power, whereas the Kokiden Consort is part of a powerful clan.

In chapter 14, when the Emperor (Genji’s half-brother) abdicates and there is a second change in reign—replaced by Reizei, Fujitsubo’s son, at about the age of 11. We can see more clearly that different people, or different factions at court, try to introduce girls to the new Emperor.

In this context, the Akashi woman is an outsider. As her child’s wet nurse thinks, she is lucky.

1/ I’m in awe of Murasaki Shikibu’s control over her hundreds of characters.

It’s difficult enough to read and keep track of them, writing is obviously much harder. The relationships are much more complicated than in War and Peace, but the characters are still distinct and memorable, in spite of their lack of names.

Brian Phillips wrote a brilliant essay about her genius, and about The Tale of Genji as a modern novel:

https://twitter.com/nguyenhdi/status/1269261354290069504

The Tale of Genji should be more widely read. It may be early for me to say, but I’m already inclined to think it’s among the best. From afar, it might seem to be a challenge because it’s from the 11th century and the characters don’t have names. However, the characters are distinct enough to remember, as long as you make notes of their changing titles and relationships.

As for it being written in the 11th century, the world depicted is certainly alien and its culture may be strange, but the techniques are surprisingly modern. The Tale of Genji forces me to rethink everything about world literature and the history of literature. Up till now, I’ve mostly read novels from the 19th century and 20th century, novels that are part of the Western canon. Now I’ve realised that in 11th century Japan, Murasaki Shikibu had already figured it all out about how to write a psychological novel.

2/ At the beginning, The Tale of Genji seems to be about an Emperor’s good-looking son who sleeps around with everyone, but it becomes darker and more complex as the story goes on.

There are some hints in chapter 1, but after a while there is a clear sense of threat, and the politics become more obvious. I understood that the Emperor didn’t want to appoint Genji the new Heir Apparent, even though he’s the favourite, because the Kokiden Consort belongs to a powerful clan whilst Genji’s mother doesn’t have anyone to back her. The Emperor means to protect Genji. I didn’t fully grasp it until later on, with the change in reign, followed by the death of the retired Emperor, and the new power dynamics.

All of Genji’s women are interesting in different ways but the affair with Fujitsubo is the most fascinating, because of the politics, and because she’s tortured by guilt and fear of discovery and revenge. Their affair is doomed from the start, and always darkened by a sense of threat.

Interestingly, Genji’s affair with Fujitsubo brings about a disruption of the hierarchy.

3/ There is a central philosophy that runs through the entire novel: mono no aware.

Mono no aware is a Japanese concept that doesn’t have an exact equivalent in English, and is usually translated as “the pathos of things” or more literally “the aah-ness of things”. It refers to the awareness of the transience of life, but doesn’t necessarily mean sorrows—it is more like the acceptance and celebration of impermanence.

From Kenkō:

“If man were never to fade away like the dews of Adashino, never to vanish like the smoke over Toribeyama, how things would lose their power to move us! The most precious thing in life is its uncertainty.”

(source)

In Japan today, the most frequently cited example of mono no aware is the love of cherry blossoms, but the philosophy goes back to Heian literature and The Tale of Genji.

“The well known literary theorist Motoori Norinaga brought the idea of mono no aware to the forefront of literary theory with a study of The Tale of Genji that showed this phenomenon to be its central theme. He argues for a broader understanding of it as concerning a profound sensitivity to the emotional and affective dimensions of existence in general. The greatness of Lady Murasaki’s achievement consists in her ability to portray characters with a profound sense of mono no aware in her writing, such that the reader is able to empathize with them in this feeling.” (source)

Reading The Tale of Genji, we’re aware of nature’s beauty and its changing nature—dew, the moon at different times of the month, blooming and falling flowers, changing seasons… There’s also a sense of transience that permeates the entire work—an awareness of the impermanence and uncertainty of life.

Genji, for all his faults, is a deeply sensitive character, and he has a profound sense of mono no aware. Up till now, he has lost 5 people close to him. Their deaths are more than plot devices to move the plot forward, and not merely characters being killed off—each death seems to have a profound impact on Genji, each death is a great loss.

4/ Here is an updated list of Genji’s women.

Spoiler alert: if you don’t want spoilers, stop reading here and go buy The Tale of Genji.

- Aoi: Genji’s first wife. He is arranged marriage with her after his coming-of-age ritual—he’s 12, she’s 16. Aoi is daughter of the Minister of the Left and the Princess, the Emperor’s sister, so Aoi and Genji are first cousins. She’s distant. They have a son known as Yugiri.

- Fujitsubo: the Emperor’s concubine, who is said to look like his dead concubine the Kiritsubo Haven (Kiritsubo no Koi), Genji’s mother. Later on, Fujitsubo and Genji have an affair, and have a child together, Reizei, who becomes Heir Apparent with the change of reign. She is Consort at the beginning, then becomes the Empress (Her Majesty), then becomes Her Cloistered Eminence (when the Emperor retires), then becomes a nun. Tortured by guilt and fear.

- Utsusemi: married to the Iyo Deputy (Iyo no Suke) and stepmom of the Governor of Kii (Ki no Kami). She is distant and plays hard to get, but that doesn’t stop Genji harassing her, using her brother Kogimi (poor kid). Associated with the cicada, because in her flight she leaves behind her gown, like a cicada shell.

- The lady from the West Wing (Nobika no Ogi): sister of the Governor of Kii and stepdaughter of Utsusemi. The first time Genji sees her, they’re playing Go together. He finds her whilst looking for Utsusemi (chapter 3), but takes her anyway, because a woman is a woman, I guess? Associated with reed because Genji attaches it to his letter. She marries the Chamberlain Lieutenant.

- Yugao: called twilight beauty. She is To no Chujo’s ex and has a child with him known as Tamakazura. 19 years old. When Genji meets her in chapter 4, she’s hiding near the house of Koremitsu, Genji’s confidant, because of To no Chujo’s wife’s jealousy. Later she becomes a victim of someone else’s jealousy.

- The Rokujo Haven (Rokujo no Miyasudokoro): widow of a former Heir Apparent. Older than Genji, neglected by him, and humiliated by Aoi’s people. Her jealousy takes the form of a spirit that fatally attacks other women.

- Murasaki: Fujitsubo’s niece and daughter of His Highness of War. Resembles Fujitsubo. Also called the lady of Genji’s west wing. 10 when Genji meets her for the first time and abducts her. She is Genji’s ideal woman project. Associated with the colour violet (murasaki).

- Suetsumuhana: also called the red-nosed woman. The Hitachi Prince’s daughter. She is ugly and boring, with nothing to say. Genji thinks she has nothing to offer, but has an affair with her anyway, in chapter 6. Associated with the safflower because of its dye.

- The Aging Dame of Staff (Gen no Naishi): an old horny staff woman for the Emperor, of about 57-58. Genji’s close friend To no Chujo also pursues her out of curiosity but she only wants Genji. Genji becomes involved with her in chapter 7.

- Asagao: daughter of His Highness of Ceremonial. I’m not sure when the affair starts. In chapter 10, she becomes the High Priestess of the Kamo Shrine, but Genji doesn’t leave her alone—when does he ever leave anyone alone?

- Oborozukiyo: sixth daughter of the Minister of the Right and sister of the Kokiden Consort (who in chapter 9 becomes the Empress Mother with the change of reign). Associated with misty moon, or moon at dawn, because of Genji’s poem. Genji starts sleeping with her in chapter 8. Later she becomes Mistress of the Wardrobe, then Mistress of Staff, then moves into Kokiden when the Empress Mother (previously Kokiden Consort) moves to Umetsubo. If I understand it correctly, chapter 10 says that she’s married to the new Emperor (Suzaku), i.e. her nephew (I know). The new Emperor knows about her affair with Genji and makes no reproaches, but doesn’t appoint her a Consort. Her father and sister get into a rage when they find out.

- Hanachirusato: sister of the Reikeiden Consort. Her sister was the late Emperor’s Consort, but not among the favourites. In chapter 11, it is subtle, but I think Genji has been involved with her. Associated with falling flowers.

My copy.

1/ One may ask why Royall Tyler, as a translator, doesn’t pick a nickname for each character and stick to it, to make it easier for modern readers. This is his explanation about the social world of The Tale of Genji, and his decision to retain the way the narrator refers to the characters:

“This feature of the original text has been retained to preserve the character and structure of the social world that the narrator brings to life. The fictional narrator speaks from within this structure, and for her, good manners require conventional discretion. As a gentlewoman to a great lady, she of course stands high in the overall population of her time, counting from peasants up, but peasants and so on do not belong to her world. Hers is that of the court, in which she has a modest place. Her language must acknowledge this place, and it must also convey the way her characters would think and talk about each other if they were real.

To put it another way, the absence of personal names from the narration is another distancing device that screens a lord or lady’s person from the outsider’s gaze. […] The way the narrator refers to people affirms less their individuality than their position in a complex of communally acknowledged relations that was of absorbing interest to all. To give the characters invariant designations (in effect, personal names) would therefore be to shift the narrator’s courtly stance toward a modern egalitarian one.”

2/ The baffling contradiction is that this social world has a strict hierarchy, but there are no real lines when it comes to sex and affairs.

What I mean is that, in today’s world, there are certain lines—most people wouldn’t have sex with their first cousins, their best friend’s partner, or children. The world of The Tale of Genji doesn’t have such “rules”.

If we look at Genji, he’s married to his first cousin (Aoi), and so far he has been involved with a married woman of lower rank (Utsusemi, the cicada woman), her stepdaughter—whom he stumbles upon whilst looking for Utsusemi (Nobika no Ogi, the reed woman), an older widow (the Rokujo Haven, the jealous woman), his close friend’s ex (Yugao, the twilight beauty, To no Chujo’s ex), an ugly and boring woman that he thinks has nothing to offer (Suetsumuhana, the red-nosed woman), his stepmother (Fujitsubo), her little niece (Murasaki), a staff woman of about 57-58 (Gen no Naishi), and his other stepmother’s sister (Oborozukiyo, the moon-at-dawn woman, sister of the Kokiden Consort). So much incest.

(A note: the Kokiden Consort is the Emperor’s wife before he marries the Kiritsubo Haven and has Genji. Their son Suzaku is the Heir Apparent, who in chapter 9 becomes the new Emperor. After the Kiritsubo Haven’s death in chapter 1, the Emperor marries Fujitsubo).

Is there anyone that Genji leaves alone?

But it’s not just him. Genji’s close friend To no Chujo chases the old staff woman when knowing that Genji is doing so. In this society it’s apparently not a thing to stay away from your close friend’s lover.

This world is messed up in other ways. For example, in chapter 8, Genji is involved with Oborozukiyo, who is intended for the Heir Apparent—i.e. her nephew. I mean, what? Is there no sense of order at all?

Keeping track of these characters is difficult enough, and requires full immersion in the novel, but Murasaki Shikibu makes them distinct and memorable. It is keeping track of relationships—seeing how characters relate to each other—that is difficult.

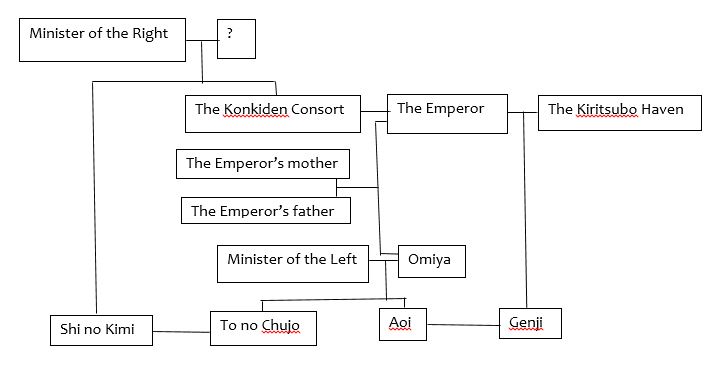

I have just realised, for example, that Genji and To no Chujo relate to each other in another way. We know that Genji is married to To no Chujo’s sister Aoi (their father is the Minister of the Left), so they are brothers-in-law. They are also cousins, because Genji is the Emperor’s son, whilst To no Chujo’s mother is Omiya, the Emperor’s sister.

At the same time, To no Chujo is married to a daughter (Shi no Kimi) of the Minister of the Right, and the Minister of the Right is father of the Konkiden Consort, so To no Chujo’s father-in-law is Genji’s stepmother’s father.

See the family tree I drew.

In other words, To no Chujo is Genji’s brother-in-law, but also Genji’s stepmother’s father’s son-in-law.

What did I just write?

In other words, To no Chujo is Genji’s brother-in-law, but also Genji’s stepmother’s father’s son-in-law.

What did I just write?

3/ Genji screws almost everyone at court, but in a discreet way, and he fears for his reputation. He often goes out in disguise, keeps Murasaki a secret, and needs others to cover up for him, such as Koremitsu’s handling of the Yugao situation or To no Chujo’s silence about his affairs. The Emperor doesn’t know about his flirtations and numerous affairs, and most people at court have an image of him very unlike his true character. Murasaki Shikibu, in a subtle way, contrasts the way Genji is seen by people not close to him, especially the Emperor, and the way he really is. She therefore makes the readers re-examine and see the irony in other people’s perception of Genji as wonderful and perfect.

Genji is definitely portrayed as imperfect, but he’s not all bad either—he does care about his women instead of playing with their feelings and throwing them away. He has sensitivity and compassion, and tries not to hurt the feelings of the women he has slept with, even if he doesn’t care about them anymore, such as the reed woman or the red-nosed woman.

In chapter 9, it upsets Genji when he hears about the skirmish between Aoi’s people and the Rokujo Haven’s people. He just wants the women to have peace, and nobody to get hurt. Later, when his first wife Aoi becomes pregnant and unwell, he understands his duty to her, but comes to tell the Rokujo Haven to make her understand and not feel neglected. Does he need to do so? Not really, but he chooses to, anyway, the same way he chooses to send expensive presents to the red-nosed woman and her gentlewomen.

In chapter 4, and then chapter 9, we can see that Genji has depth of feeling, and sincerely cares for the women in his life.

4/ One would ask, what about jealousy? Genji has so many women, there must be some jealousy.

So far, the image of jealousy in The Tale of Genji is in the character of the Rokujo Haven. However, she is different from Hoạn Thư (Lady Hoan) in Nguyễn Du’s Truyện Kiều, who becomes an archetype in Vietnamese culture.

Hoạn Thư’s jealousy is the possessiveness, anger, and malice of a first wife—she has more legitimacy and power, and looks down on the other woman (Kiều). In a similar positon in The Tale of Genji would be the Kokiden Consort, but she cannot compare to Hoạn Thư in cleverness and maliciousness, at least so far.

The Rokujo Haven’s jealousy is the jealousy, misery, pain, humiliation, and bitterness of a lover—a neglected, helpless lover. As herself, she is helpless and does not dare to claim anything, but her jealous rage takes the form of a spirit to fatally attack other women, even while she’s alive.

This is something I’ve never seen in a novel before, but it works so well in The Tale of Genji that it not only doesn’t appear at all out of place, but it also leads to such evocative images and powerful moments in the novel, especially in chapter 9.

Why did Virginia Woolf, in her review of Volume I (Waley’s translation), think the novel lacked force?

5/ To those unfamiliar with the story, I should note that Genji’s relationship with Murasaki is not based on paedophilia—he doesn’t have a particular interest in children, Genji is no Humbert Humbert. His attraction to her is because of her resemblance to Fujitsubo, his stepmother and her aunt, and his relationship with her is rooted in the idea of teaching and moulding her into a perfect wife.

Genji sees Murasaki for the first time when she’s 10, and brings her home, but doesn’t have sexual relationship with her until chapter 9—when she’s about 14-15. In today’s understanding, she’s still a child, and most readers wouldn’t help feeling grossed out, but this is 11th century Japan.

As I have said before, because this world is so alien and operates by such different rules that it’s hard to evaluate Genji’s actions and know Murasaki Shikibu’s thoughts about her characters and their world. However, we can see that other characters are shocked by his interest in the girl and disapprove of his abduction, and he himself has to keep it a secret for several years.

We can also see that their first sexual experience is unexpected, shocking, and unpleasant to the girl, and that Genji doesn’t understand it.

Valerie Henitiuk wrote an essay, comparing 3 translations, imagining a Genji translated by Virginia Woolf, and raising the question of male vs female translators: https://twitter.com/nguyenhdi/status/1267902864690642951

In it, she does write about the differences between the original and the translations regarding the scene with Murasaki in chapter 9.

The book, meanwhile, is getting better and better.