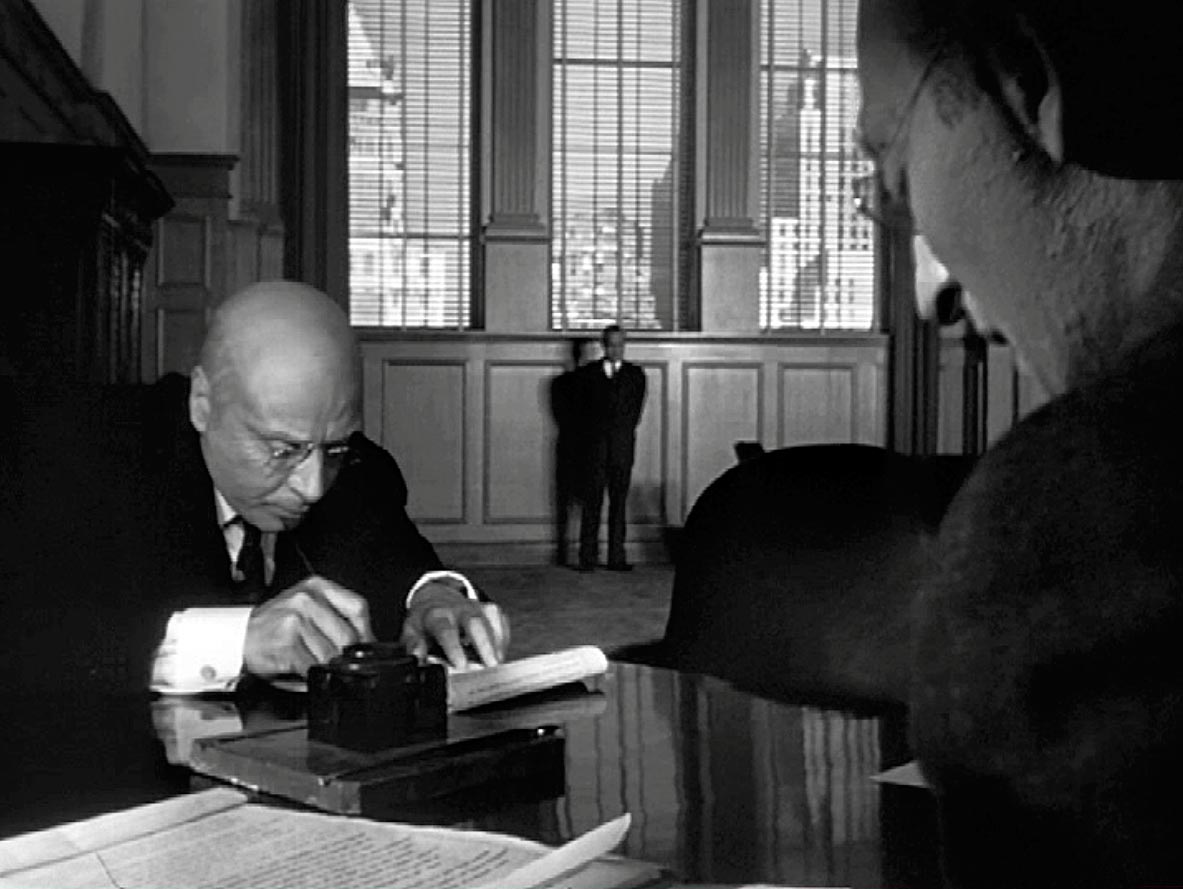

See what he says about Citizen Kane and deep focus (i.e. foreground, middleground, and background are all in focus):

“The depth of field Welles and Toland wanted to achieve would offer the viewer a larger expanse of clearly visible space, and consequently a greater choice of objects contained in the same shot. Previously—and even subsequently—the image on the screen had tended to highlight the person or object to which the filmmaker wanted to draw attention, leaving everything surrounding it or behind it indistinct. Welles, however, wanted to experiment with different spatial shots. Toland therefore worked mainly with a Cooke 24mm lens with a very short focal length, which captured a far greater amount of light and gave him a far greater depth of field. The use of Eastman Kodak Super XX film (4 times more sensitive than conventional film stock) and a reliance on powerful arc lamps rather than the softer tungsten lamps, substantially enhanced the deep focus effect of a scene.”To most people, that is probably too technical and provokes nothing, but to me, it is delicious.

Mereghetti goes on:

“This revolutionary approach to lighting brought about other changes, because wide-angle lenses such as the Cooke 24mm enlarged the image both horizontally and vertically, thus forcing the filmmaker to concentrate on the ceilings as well as the other parts of the set. This led to a totally new conception of scenic spaces and camera angles; Welles could use ceilings not only to conceal a larger number of microphones (which enabled him to obtain an unprecedented depth of sound), but also to enhance the dramatic power of a particular scene. A low ceiling that appeared to be ‘crushing or ‘imprisoning’ the characters heightened the impression of their spatial confinement.The deep focus not only creates a richer image, with everything in frame sharp and clear. It also allows Welles to view space differently, so he might keep everything we need to see in 1 shot instead of breaking up the action into a series of shots; he also has greater freedom with staging and blocking, and plays with the z-axis.

However, the experiment with deep-focus photography should not be interpreted as a quest for greater realism or an opportunity to adapt the camera lens to the human eye, which always brings into focus the space that surrounds it. Welles regarded it as an essential tool for devising a new way of reading the spaces within the shot, for creating an articulated system of spatial references, a new ‘symbolic form’ with which to subvert the conventions of the medium. This is apparent at the beginning of Citizen Kane, where the narrator (Welles), describing the approach to Xanadu and then the discovery of Kane’s death, immediately puts the viewer on his guard and provides a clear demonstration of a new ‘form’ of cinema.”

My friend Himadri places Billy Wilder above Orson Welles, but the passages above explain why Welles belongs to the top rank of directors whilst someone like Billy Wilder doesn’t. Much as I love Billy Wilder’s films, he was using the tools and techniques that were already there, to tell great stories, whereas Orson Welles, like Bergman or Fellini, was exploring the possibilities of cinema, pushing for new ways of telling a story, and challenging conventions, and he changed cinema. Style is not more important than substance, I doubt that I’d get along with auteurists, but directors are not mere storytellers. I might feel more about Billy Wilder’s work (especially Sunset Boulevard, The Apartment, Witness for the Prosecution, and perhaps also The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes), but rank Orson Welles more highly.

Having said that, I love Welles not only because of his style and revolutionary techniques, but also because of the content, the complex, multi-faceted characters, and the themes.

interesting... i wonder how short a focus can be before it returns negative results...

ReplyDeleteLittle focus would just make it blurry.

DeleteI do actually take your point. Citizen Kane innovated new techniques with which to communicate the drama, whereas Wilder used techniques that had already been pioneered and developed. My question is whether that, in itself, makes for a greater work of art. For while there is clearly great artistry in pioneering new techniques, is there not similarly artistry in using well what is already available? Is not getting to the top of Everest using traditional climbing gear as remarkable as inventing a machine to take you to the top?

ReplyDeleteHaydn was an innovator: Mozart wasn’t. Sterne was an innovator: Fielding wasn’t. “Waiting for Godot” innovated: “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” didn’t.

The innovatory brilliance of Sterne, of Haydn, of “Waiting for Godot”, aren’t in question. What I am questioning, though, is the assertion that making use of what is already available is necessarily artistically inferior. For making *good* use of something already available is as artistically valid as inventing something new, and can yield results equally remarkable. And ultimately, it is by the results that we judge the works. By their fruits shall ye know them, as the Good Book says.

I personally rated Wilder above Welles simply because Wilder has made *more* great films than Welles has done. This, I appreciate was not Welles’ fault, as he was shunned by the studios and had to work hard to raise funds for his projects. But while I can name a dozen or so great films by Wilder, I am restricted to only two or three great films by Welles. Of course, one may as “Isn’t two or three a lot?” Yes. I don’t mean to denigrate Welles. But Wilder making such superb use of techniques that were already there is as remarkable an achievement as inventing new ways to get to the top of Everest.

"Haydn was an innovator: Mozart wasn’t. Sterne was an innovator: Fielding wasn’t. “Waiting for Godot” innovated: “Long Day’s Journey Into Night” didn’t."

DeleteI see your point, but at the same time, film is more technical than literature and classical music.

I also see what you mean about personally rating Billy Wilder above Welles, and agree that Wilder has made more great films. But I was explaining why the general consensus, or at least among critics, is that Welles is seen as greater and more important to cinema, so to speak. He's also more influential.

I suppose that Billy Wilder might have touched more people, emotionally, but Orson Welles had more influence on cinema and other filmmakers. You say 2-3 films, but Citizen Kane alone is a remarkable achievement already, considered as the greatest film ever made, and it was his 1st film!

But as I said, it's not only about style and technical aspect that I love Welles.

DeleteI'd pick Billy Wilder or Clint Eastwood over someone like Lars von Trier any day.