1/ The greatest novel I’ve read this year is easily The Brothers Karamazov by Dostoyevsky. Sometimes I look at the suffering around the world, and around me, and think about the “I’ll return the ticket” chapter.

Not hard to see why some people think The Brothers Karamazov is the greatest novel ever written.

2/ The greatest non-fiction book I’ve read this year is Gary Saul Morson’s Wonder Confronts Certainty.

The book was a birthday present from Tom of Wuthering Expectations and it was just my thing, exploring Russian literature and history of ideas—from the period leading up to the Revolution, to the Stalinist years—and the big questions.

Gary Saul Morson also wrote about intellectuals’ bloodlust and love of violence and embrace of revolution for the sake of revolution, which I didn’t expect to see playing out across the West just a few months later.

3/ 2023 has been a strange year. Things fell apart. My life took a new turn.

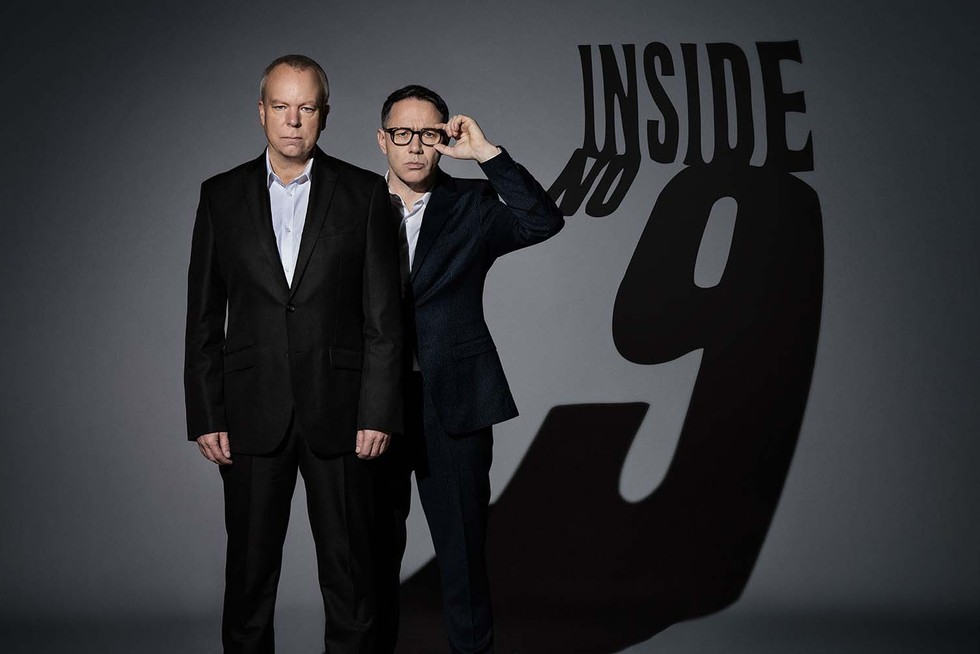

Looking back at my reading and viewing in 2023, I realise that I didn’t read many novels, nor watched many films. Busy with work. Unable to concentrate. And all that. So I mostly binged on The Mentalist and watched Inside No.9 and read short stories.

The writer who has meant the most to me this year, on a personal level, is Chekhov. Tolstoy continues to be the prose writer I admire the most—Anna Karenina and War and Peace are part of my mental furniture—but Chekhov is the writer to whom I feel the closest.

And yet here’s a paradox: Chekhov brings comfort in difficult times but might also make me pessimistic. Tolstoy and Shakespeare don’t have that effect.

4/ I read Hamlet for the third time this year and finally something clicked, finally I grasped something that had previously eluded me. I love the play, and love the Kevin Kline production.

5/ In 2023, I discovered Mishima Yukio, Alice Munro, Flannery O’Connor, and Isaac Babel.

Flannery O’Connor is one of the few short story writers about whom I do not think “not quite Chekhov but…”. I think that when reading Alice Munro or Isaac Babel or Balzac, but not when reading O’Connor. She’s her own thing. And she is a great writer.

6/ For a long time, my idea of Russia was either Tolstoy’s Russia or Soviet Russia. Isaac Babel’s Russia, now Ukraine, is very different as he wrote about Jews, Jewish gangsters, and pogroms.

I was reading Odessa Stories on my Prague work trip: it was strange, and horrible, to read Isaac Babel’s depiction of the 1905 pogrom, then see the memorial to Holocaust victims in Bohemia and Moravia, and then look at the internet and see the antisemitism taking hold of many people and institutions in the West today.

Now reading Red Cavalry.

I’d like to read more Jewish literature.

Anyway, thanks for reading my blog, and thanks for all the interesting conversations here. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to you all!