Dracula begins with the journal of Jonathan Harker, who is a diligent diarist. There are entries for 3/5, 4/5, 5/5, 7/5, 8/5, 12/5, 15/5, 16/5, 18/5, 19/5. Suddenly there's a jump straight to 28/5, followed by a 31/5 entry. Again there's a lapse, the next entry is dated 17/6, then Harker writes on 24 and 25/6, then 29 and 30/6, and Harker's narrative ends.

Perhaps on those days he doesn't write. Or maybe the entries have no relevance as documents and are disregarded altogether. It makes me wonder, however, about what he does during those days; in fact, what he does the whole time he's at the castle. At the beginning he does write down, in details, the paperwork and discussions with Count Dracula. Afterwards, there is no more- what does he do when not watching the weird creatures of the castle or trying the locked doors?

After Harker's narrative is the correspondence between his fiancée Mina Murray and her friend Lucy Westenra between 9/5 and 14/5. This placement is an understandable choice, because Bram Stoker now introduces a bunch of new characters and a different setting and another storyline. There's another shift with Dr Seward's diary (kept in his fancy phonograph) and the introduction of Renfield. The date is 25/5.

After some exchanges between the men, Stoker gives us Mina's journal. The 1st date is 24/7, about a month after the last entry in Harker's journal. After that is 1/8. This is when she mentions Jonathan.

"Lucy and I sat awhile, and it was all so beautiful before us that we took hands as we sat; and she told me all over again about Arthur and their coming marriage. That made me just a little heart-sick, for I haven’t heard from Jonathan for a whole month."

Then her narrative, before we know much of her, is cut off. Stoker directs our attention to Dr Seward and Renfield. The dates in the diary are 5/6, 18/6, 1/7, 8/7, 19/7 and 20/7. We're hooked. At least, I'm hooked. This business with Renfield is fascinating, I don't know what he has to do with anything in the plot, but it sure is fascinating, but before anything happens, Stoker brings Mina back. Now the date is 26/7, followed by 27/7. Here she talks about worries for her fiancé, and for Lucy's sleepwalking. What is this moving back and forth? The next entry is dated 3/8.

Why this arrangement? I'm quite confused.

Dracula makes me think of The Woman in White.

Both are novels-as-documents. How many novels of this type have I read lately? Frankenstein is slightly different- the book is a series of letter from Walton to his sister, but embedded in this narrative is Frankenstein's narrative, which in turn frames the creature's narrative (reminiscent of The Tenant of Wildfell Hall- the whole novel is 1 letter from Gilbert Markham to a friend, and within this letter is Helen's diary). Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde isn't strictly an epistolary novel, though there are 2 chapters at the end that are letters. Only The Moonstone is another novel composed of a series of documents: reports, letters, diary excerpts, articles, etc. Like Dracula and The Woman in White.

It can be felt that in Dracula, the various writings are not put together by Bram Stoker for the benefit of the reader (multiple viewpoints) like A Hero of Our Time for instance, but collected and organised by the people in the book, as in the 2 novels by Wilkie Collins.

Another thing that unites Dracula and The Woman in White on the surface is the terror, or rather, the mystery and suspense. There are more similarities. Jonathan Harker coming to a strange house and becoming imprisoned in it is reminiscent of Marian and Laura being imprisoned in Percival Clyde's house. If Harker is Bram Stoker's Marian, his Count Fosco is Count Dracula. Fortunately our Jonathan Harker isn't as dim-witted and slow to understand as Marian Halcombe. He observes and notices everything and understands things quickly, which a few times makes me wonder if it's plausible- I mean, if any intelligent person under such circumstances would come to such conclusions, or it's only Bram Stoker answering questions he previously raised and making it easier for us. No, it's probably logical- I can't say because I have something akin to hindsight, I know what Dracula is.

Anyway, I must write again, Harker's smarter than Marian. Look at chapter 3, entry for 15/5:

"When I had written in my diary and had fortunately replaced the book and pen in my pocket, I felt sleepy."

That's the way to do it, Marian. Hide your writing away before you may doze off. Why leave everything there for the Count to see.

Wish I could say, after some time's silence, "Back from [some fascinating city]", but can't. I've been busy, that's all- sunbathing, working, watching films, catching up with fb, following a murder case in VN, dealing with some problems (lots of things happened, and there was a creep)... In spare time I read a Tolstoy short story collection, and Flaubert's 3 Tales, just didn't write about them. As you can see, Effi Briest has been put aside.

I'm reading Dracula at the moment.

One cannot have a "fresh" reading of Dracula, everyone knowing something about it. The same goes with Frankenstein or Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, both of which I read earlier this year. The feeling is strange- the consciousness that I'm reading for the 1st time a very famous and influential book, the expectation of finding it as good as it is said to be, the wish to compare it to the preconceptions created by popular culture. Sometimes they turn out to be misconceptions. Take Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, discussed here, here and here- Jekyll and Hyde are not 2 beings in the same body, 1 good, 1 evil, and Hyde is actually smaller than Jekyll. Or Frankenstein, discussed here, here, here, here and here, Frankenstein is the scientist, not the monster, but Frankenstein is a monster, and the experiment is in fact not a failed experiment as people suggest.

Luckily my so-called knowledge of these 3 books comes from who knows where, not from film adaptations (if I've watched one, I've forgotten it). Tom at Wuthering Expectations once wrote "How many first-time readers miss the actual story on the page in front of them while looking around for Igor and the pitchfork-wielding peasants and "Puttin' on the Ritz"?" That isn't my problem here. My problem is something else.

Look at the 1st chapter of Dracula. Bram Stoker uses lots of details and images to create a horrifying atmosphere:

- A dog howling all night under window.

- Queer dreams.

- People's looks of fear, and whispers ("Satan", "hell", "witch" and "werewolf" or "vampire").

- St George's Day.

- The sign of the cross, a charm or guard against the evil eye.

- The gift of a crucifix.

- The prevalence of goitre.

- Peasant's cart with long, snake-like vertebra.

- Dark firs that stand out against the snow.

- Great masses of greyness.

- Steep hills, ghost-like clouds.

- The driver's haste, and fellow passengers' excitement.

- Dracula's man, who has "a hard-looking mouth, with very red lips and sharp-looking teeth, as white as ivory", and strong, cold hands.

- Feeling that the calèche goes over and over the same ground.

- A dog howling, "a long, agonised wailing, as if from fear", followed by several other dogs.

- Wolves.

- Horses trembling, snorting and screaming with fright.

- A heavy cloud passing across the face of the moon; darkness.

He causes fear and builds up tension and prepares readers for greater horror ahead. Foreshadowing device. Victorian readers didn't know what was coming, they were scared and their imagination was filled with possibilities and they tried to guess what was going on and what was going to happen next and were eager to find out. I have a faint idea. To Victorian readers, Dracula is only a name, which they take and accept neutrally. To me, the name carries with it so many associations and images, the name is tinted, and tainted. I'm reading it, but at the same time, I find myself looking for something.

Let's see how it goes.

(originally posted on 17/10/2014).

Such a list only shows how little I've watched (very often, an excellent film is not mentioned here simply because I haven't watched it), but I'm shamelessly making and publishing it anyway. The ones in bold type are masterpieces and strong favourites, and will certainly remain in the list (in other words: will not be removed at any cost), the other films can be replaced when I discover/ remember something greater.

- The 40s:

The Great Dictator (1940)

The Philadelphia Story (1940)

Casablanca (1942)

Gaslight (1944)

Brief Encounter (1945)

It's a Wonderful Life (1946)

The Killers (1946)

The Best Years of Our Lives (1946)

The Bicycle Thief (1948)

The Heiress (1949)

- The 50s:

All about Eve (1950)

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

In a Lonely Place (1950)

A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

On the Waterfront (1954)

The Killing (1956)

Witness for the Prosecution (1957)

12 Angry Men (1957)

Vertigo (1958)

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

- The 60s:

The Apartment (1960)

Psycho (1960)

Vivre sa vie (1962)

The Insect Woman (1963)

8 ½ (1963)

The Woman in the Dunes (1964)

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

My Fair Lady (1964)

Blowup (1966)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

- The 70s:

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970)

The Godfather (1972)

Last Tango in Paris (1972)

The Godfather Part II (1974)

The Conversation (1974)

Chinatown (1974)

Dog Day Afternoon (1975)

Scent of a Woman (1975)

Taxi Driver (1976)

Autumn Sonata (1978)

- The 80s:

Raging Bull (1980)

On Golden Pond (1981)

Sophie's Choice (1982)

Scarface (1983)

Ran (1985)

Rain Man (1988)

The Accused (1988)

A Short Film About Love (1988)

My Left Foot (1989)

Monsieur Hire (1989)

- The 90s:

Goodfellas (1990)

The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Raise the Red Lanterns (1991)

A Few Good Men (1992)

To Live (1994)

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

Titanic (1997)

Happy Together (1997)

Central do Brasil (1998)

Magnolia (1999)

- The 2000s:

Memento (2000)

À la folie... pas du tout (2002)

The Pianist (2002)

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter... and Spring (2003)

2046 (2004)

Million Dollar Baby (2004)

Brokeback Mountain (2005)

There Will Be Blood (2007)

Before the Devil Knows You're Dead (2007)

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2007)

Comment!

1/ The Godfather (1972)

2/ The Godfather Part II (1974)

3/ Goodfellas (1990)

4/ Mean Streets (1973)

5/ Gangs of New York (2002)

6/ Pulp Fiction (1994)

7/ Scarface (1983)

8/ Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

9/ Infernal Affairs (2002)

10/ Bonnie& Clyde (1967)

Witness for the Prosecution (1957)

12 Angry Men (1957)

Anatomy of a Murder (1957)

A Few Good Men (1992)

Fracture (2007)

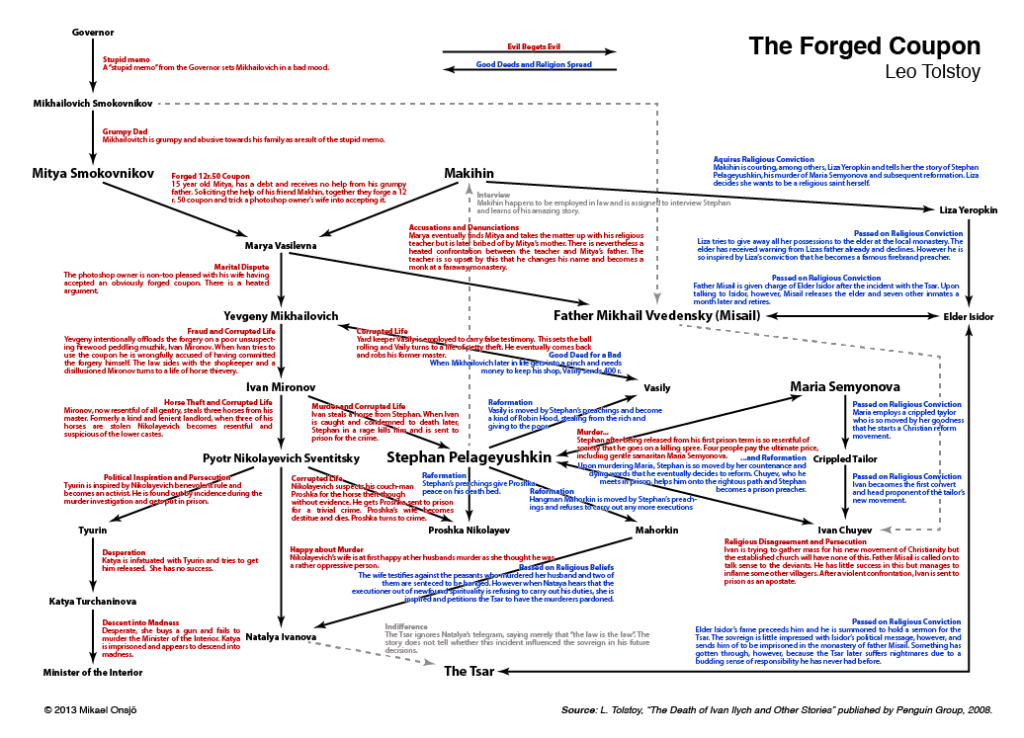

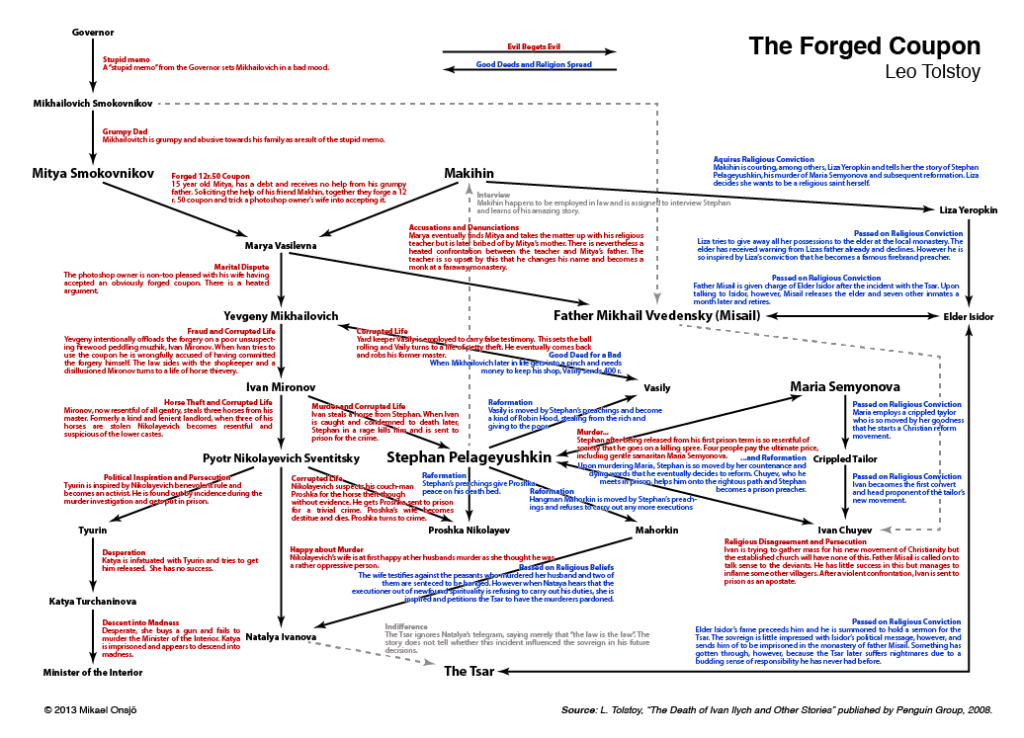

After reading Tolstoy's "The Forged Coupon" I drew a diagram of events and effects.

But then I found another, and better, one. Why not steal it? So here it is:

https://odinlake.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/tolstoy-the-forged-coupon2.pdf

1 thing leads to another. Evil begets evil. As written on the back cover of my Penguin copy The Death of Ivan Ilyich and Other Stories, the story "shows a seemingly minor offence that leads inexorably to ever more horrific crimes".

It would be simplistic, however, to say that "The Forged Coupon" is about how evil begets evil. Every single person in the story who does wrong makes a conscious choice to do wrong. These characters, when suffering a wrong, transfer the loss to someone else or seek revenge or develop a hatred against the whole world or get led astray, and they do so because they don't know they have a choice, because they think that's the way it should be. They may react in a different way, and don't. They may choose another path, and don't. It's unlike "Polikushka", in which the disaster is caused by chance, by external circumstances. If "The Forged Coupon" is more like a parable than a novella of the realist tradition, the moral is not only that one shouldn't commit even a minor offence (such as forging a coupon) because it may lead to a series of crimes, but also that one has reason and free will and under unfortunate circumstances can choose to be bad, like those characters in the story, or to be good. They only come to understand it in part 2 of the story. Despite the feeling of contrivance now and then, as this is a strongly didactic piece written in Tolstoy's last years, it is a very good story.

English translation (by William A. Cooper):

Mrs von Briest asks "Don't you love Geert?".

Effi responds "Why shouldn't I love him? I love Hulda, and love Bertha, and I love Hertha. And I love old Mr. Niemeyer, too. And that I love you and papa I don't even need to mention..."

Original German by Theodor Fontane:

"Liebst du Geert nicht?"

"Warum soll ich ihn nicht lieben? Ich liebe Hulda, und ich liebe Bertha, und ich liebe Hertha. Und ich liebe auch den alten Niemeyer. Und daß ich euch liebe, davon spreche ich gar nicht erst..."

Norwegian translation (by Lotte Holmboe):

The mother asks "Er du ikke glad i Geert, vennen min?".

Effi replies "Hvorfor skulle jeg ikke være glad i ham? Jeg er glad i Hulda og i Bertha og Hertha- og i gamle Niemeyer også, for den saks skyld. Og at jeg er glad i dere, ja, det behøver jeg ikke si engang..."

The reason I start with the English version is that in English the sentence "I love you" encompasses different meanings and can be used for family members and close friends as well as for lovers. In Norwegian, there's a distinction between "Jeg elsker deg", used by people in a romantic relationship, and "Jeg er glad i deg", which can be said by a mother or a father to a child and vice versa, or by a friend to a friend, etc. Spouses can also say "Jeg er glad i deg", but people definitely don't say "Jeg elsker deg" when it's not romantic love (unless it's a joke, of course, but that doesn't count).

Is this important? Yes. Because if Mrs von Briest asked "Elsker du ikke Geert?", Effi's answer would be quite different, I thought.

Therefore I decided to check the German original. All right, I don't speak German. A few helpful sites say that German, which is closer to Norwegian than to English, makes a distinction between "Ich liebe dich" and "Ich hab dich lieb", which, according to the explanations, seem to be equivalents of "Jeg elsker deg" and "Jeg er glad i deg" respectively. Now that might look odd, since Effi takes the romantic word and uses it in the unromantic sense. Looks like she deliberately bends the word to evade what she knows her mother really asks, to avoid saying that she doesn't love Geert.

What do you think?

We all, in varying degrees, suffer from some illusion about ourselves.

I was foolish enough to think myself capable of reading Effi Briest in Norwegian! However, stubborn as I am, I'm still struggling and currently on page 39 (beginning of chapter 7), moving back and forth between the Norwegian book borrowed from the library and the English e-book (have I said I dislike e-books?).

What did I know about Effi Briest? Theodor Fontane's masterpiece, said by some to be his greatest book. 1 of Thomas Mann's selections if one had to reduce one's library to 6 novels. A German novel that is very different from typical 19th century German novels. An unhappy family story. An adultery novel, often compared to Anna Karenina and Madame Bovary.

Therefore I was looking for the signs. And there they were. Some are Effi's traits: her youth and childlikeness (17 years old, plays with her friends in the 1st scenes like a child), her vitality, her restlessness and wish for amusement and change, her dislike of ennui, her haughtiness, and hastiness. She's a daughter of a man who doesn't seem particularly intelligent and a woman who appears to be the pragmatic and mercenary kind, placing lots of importance on wealth and social status. She wants the best, and if unable to have the best, she can forego the 2nd best, because it means nothing to her.

Most notably, Effi doesn't seem to care much about love. I was confused for a while as to why she said yes to Geert von Innstetten and, believing I had missed something on account of my broken Norwegian, I checked the English version and found hardly anything. Fontane doesn't enter Effi's mind. Geert comes, then all of a sudden Mrs von Briest tells her daughter of the proposal, and all of a sudden Effi accepts it, and the chapter ends. It becomes clearer later, that she does because he's "perfect", with good looks, social status and wealth, because he's "a man with whom [she] can shine and he will make something of himself in the world". When her mother asks "Don't you love Geert?", she says "Why shouldn't I love him? I love Hulda, and I love Bertha, and I love Hertha. And I love old Mr. Niemeyer, too." If it seems problematic on her side, so does it on Geert's side, even though we don't have his perspective. It doesn't sound like a good thing when a man asks to marry the daughter of the woman he once loved and couldn't have.

In addition to all that, Effi's parents have some misgivings about the marriage.

Fontane also sets up some other signs, some foreshadowing. 1 is the affair of Pink the overseer and the gardener's wife. Another is the funeral of the gooseberry hulls- Effi talks about sinking and, as though Fontane fears it isn't enough, refers to women who are thrown overboard for infidelity.

These are just some notes. Who knows if I'll finish the novel or not. Think how many times I put it down and wanted to give up.