1/ A brief summary: on the plot level, Kokoro by Natsume Soseki is about a young unnamed student and his friendship with an older man that he calls Sensei; on a deeper level, the novel, published in 1914, deals with the cultural shift from one generation to the next and the transition from the Meiji era to the modern era in Japan, with its various conflicts. The novel also has other themes such as isolation, egotism, and guilt.

In terms of structure, Kokoro has 3 parts, but the first 2 parts, “Sensei and I” and “My Parents and I”, form the first half of the book—a sort of memoir narrated by the student. The final part and second half of the book is called “Sensei’s Testament”—a long letter from Sensei to the student.

The central character therefore is Sensei—in the first half, we see Sensei through the eyes of the student, and later, he speaks for himself and recounts the story of his past.

2/ In the previous blog post, I wrote that I didn’t know what Sensei and the student generally talked about, how he viewed things, why the student seemed to admire, even worship him almost. This is a man who hasn’t been doing anything since graduating from university.

It is perhaps deliberate that we don’t see the student’s Sensei clearly—his perception of the man is perhaps obscured by adoration.

Near the end of the student’s narration, Sensei starts to appear to be an egotist. The young man sends him letters, he never replies. The young man asks him for some job or position to reassure his sick father, he never says a word. All of a sudden, he sends a telegram asking the young man to come and see him in Tokyo, even though the man is at home taking care of his seriously ill father.

Under such circumstances, knowing that the young man has enough anxiety to deal with, Sensei sends him a long letter, in which the recipient catches a glimpse of this line:

“When this letter reaches your hands, I will no longer be in this world. I will be long dead.” (Ch.54)That’s not exactly considerate, is it?

And how does Sensei justify his silence?

“Truth to tell, I was just then struggling with the question of what to do about myself. […] I was like a man who rushes to the edge of a cliff and suddenly finds himself gazing down into a bottomless chasm. I was a coward, suffering precisely the agony that all cowards suffer. Sorry as I am to admit it, the simple truth is that your existence was the last thing on my mind. Indeed, to put it bluntly, the question of your work, of how you should earn your living, was utterly meaningless to me, I didn’t care. It was the least of my problems…” (Ch.55)What a self-absorbed arsehole.

3/ The style in the second half is different.

“You revealed a shameless determination to seize something really alive from within my very being. You were prepared to rip open my heart and drink at its warm fountain of blood. I was still alive then. I did not want to die. And so I evaded your urgings and promised to do as you asked another day. Now I will wrench open my heart and pour its blood over you. I will be satisfied if, when my own heart has ceased to beat, your breast houses new life.” (Ch.56)Intense.

These lines somehow make me think of Ingmar Bergman.

4/ The second half of Kokoro is a character study of an egotist—Sensei speaks of his past and the events that have shaped him into a bitter, vindictive man who distrusts the world, tortures himself with guilt, and has an obsession with death.

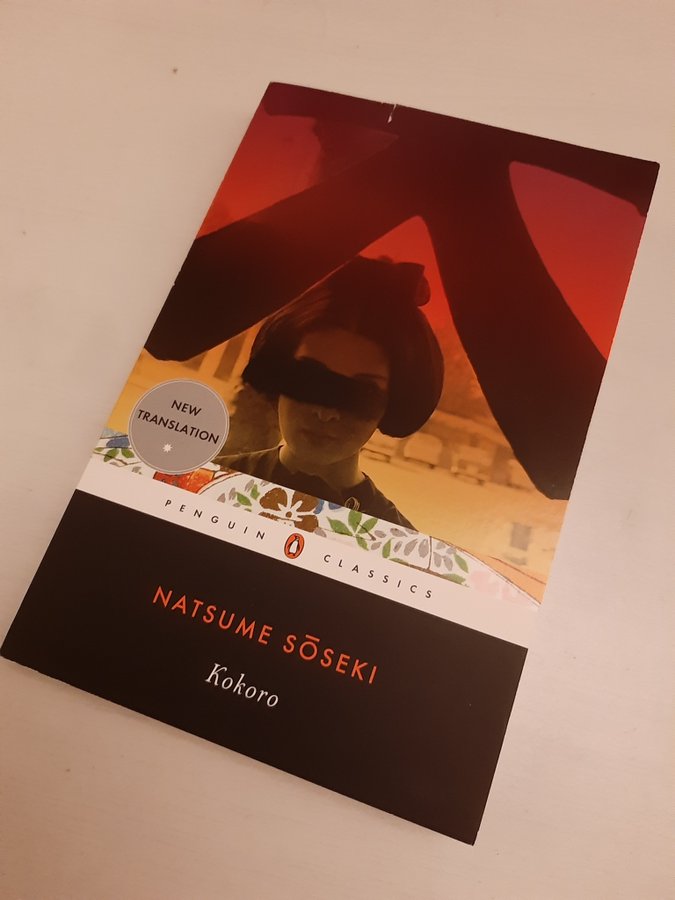

It is captivating, and even though I read it in translation (by Meredith McKinney), it works because Soseki creates a different voice for Sensei. The student seems more curious, open, and calm—he’s unable to grasp Sensei’s moral anguish and sometimes appears innocent and naïve, but sometimes also shows great perceptiveness. Sensei, even as a young man, sounds suspicious, angry, even highly strung sometimes.

The novel becomes more engrossing when we’re introduced to Sensei’s close friend at university, who is known as K. Both of them are colourful characters and therefore more fascinating than the first narrator of the novel. In some ways, the friends seem to be opposites—Sensei doesn’t have any clear direction in life whereas K decides to become a Buddhist monk and focuses all his energy on that one thing; K has a strong will and dominates Sensei; K has great self-assurance and seems indifferent to everything unconnected to his aspirations, whereas Sensei is jealous, anxious, and tortured by doubt.

It is fascinating how at the beginning, K appears to lack some kind of humanity, in his high ideals, strong will, and single-mindedness, so Sensei tries to humanise him, to “infuse in him [his] own living heat” (ch.77).

“It seemed clear to me that his heart had rusted like iron from disuse.” (Ch.79)Sensei tries to soften him by introducing him to the opposite sex.

“His sights were fixed on far higher things than mine, I’ll not deny it. But it is surely crippling to limp along, so out of step with the loft gaze you insist on maintaining. […] As a first step in the task of humanizing him, I would introduce him to the company of the opposite sex. Letting the fair winds of that gentle realm blow upon him would cleanse his blood of the rust that clogged it, I hope.” (ibid.)But once it happens, there comes out the dark side in Sensei—his vindictive nature, his suspicion and jealousy, and his pettiness.

If in the first half of Kokoro, the student is relatively soft and doesn’t have much of a presence, in the second half, we have 2 formidable, impressive characters, balancing off each other.

As K softens and becomes more human, Sensei becomes consumed with jealousy, and turns to cunning.

5/ The characters in Kokoro, especially Sensei and K, are vividly drawn, and Natsume Soseki displays keen psychological insight.

Spoiler alert: those of you who haven’t read Kokoro are warned that from this point on, I will discuss some significant plot points in the novel.

6/ One of the ideas in Kokoro is the idea of weakness—as Sensei says over and over again throughout his testament, he is weak and K is strong.

I don’t really think that’s the case. K isn’t strong as much as he is stiff, hard, inflexible—he can’t bend, that’s why he breaks.

7/ I suppose that any foreign reader of Japanese literature at some point must ask: what’s up with the Japanese and suicide?

So why does K kill himself?

Here is what Sensei says:

“At the time it happened, the single thought of love had engrossed me […] I had immediately concluded that K killed himself because of a broken heart. But once I could look back on it in a calmer frame of mind, it struck me that his motive was surely not so simple and straightforward. Had it resulted from a fatal collision between reality and ideals? Perhaps—but this was still not quite it. Eventually, I began to wonder whether it was not the same unbearable loneliness that I now felt that had brought K to his decision.” (Ch.107)I think “a fatal collision between reality and ideals” must be a factor—K has alienated both his biological family and adoptive family in his pursuit of spiritual ideals and focuses all his energy on his aspirations, seeing everything else as meaningless and frivolous, only to find himself now wavering and lost because of love. But I think the more important reason is his unbearable loneliness. K has been renounced by both families and has no other friends, and his only friend, who should be helping him face his crisis, gets engaged behind his back to the first woman K ever loves. It is a betrayal and an abandonment at the same time.

Sensei’s unbearable loneliness over the years, however, is a different kind. It is the isolation and suffering caused by guilt and self-disgust, by the thought that he doesn’t deserve life and happiness, by the thought that he is getting punished.

8/ Sensei writes to the student so the young man can learn from his past (and not make the same mistakes). But at the same time, Sensei can finally write it all down and face the truth, and he may die thinking that at least there’s one human being he could have trusted, to whom he can confess all his guilt.

9/ As the structure of the book has the first half narrated by the young man and the second half being Sensei’s testament, we don’t know what the young man does after reading the letter. All we know is that after getting a glimpse of some significant words in the letter, he jumps on a train, abandoning his dying father for the already dead father figure. I imagine that a Western writer would probably return to the young man after Sensei’s testament, and bring about, or at least suggest, a resolution of some kind. Soseki doesn’t. Kokoro has an inconclusive ending.

However, the novel doesn’t feel unfinished, or lacking something. Somehow it feels right that it ends with Sensei’s death (or rather, his last words). To Sensei himself, his death is associated with the end of the Meiji era—he goes with the spirit of the Meiji era. After him, the student would have a new beginning.