I've finished reading Villette.

It is a very different book from Jane Eyre. Yes there's passion, there's intensity, there's a woman alone who earns her own living, but, for 1 thing, Jane Eyre and Lucy Snowe are different- though both are introverted in nature and at the same time forced by circumstances to be alone, both have to earn money for themselves so as not to burden anyone else, Lucy's more withdrawn, more solitary, alienated from her surrounding and suffering from loneliness for great portions of the book. That makes the whole tone of Villette different, the mood, the atmosphere different. Jane undergoes hardships and injustice and suffering, but as a child she's close to Helen Burns, later when she works as a governess she's close enough to Adele and finds in Rochester a soulmate. She and Rochester have experience and know much about life from suffering, so they understand each other- in fact, their 1st meetings already show a sense of understanding only between themselves, as Mrs Fairfax cannot join their conversation, nor know what they're talking about. Generally quiet, but Jane can be frank and open, many times she speaks out her mind and on a few occasions has an outburst.

Lucy most of the time keeps things to herself. Indeed, she does give Ginevra a lecture now and then, indeed, she does talk about Protestantism and Catholicism, indeed, she once talks to a priest of her loneliness, but most of the time she maintains self-control, keeps everything to herself and endures everything alone. She never opens up her soul to anyone. She never has an outburst. She rarely speaks frankly and openly about her private life and feelings. Lucy even keeps a distance from readers- I've never seen any narrator so secretive, she keeps withholding information.

As I picture the characters in my mind, Lucy and Jane are alike in that their faces are not lively, cheerful, sociable faces, but one can see some fire, some intensity in Jane's eyes, yet nothing, nothing at all in Lucy's. They're just tranquil.

I don't think Lucy truly has an attachment to anyone in Villette. Ginevra doesn't know anything about her. Madame Beck sees her as an employee and is seen as a employer. Graham and Polly respect her, care for her and confide in her, but there's always a wall Lucy builds between them and herself, she listens but seldom talks, and they are ignorant of her feeling and suffering. Later she becomes closer to and seems to fall in love with Paul Emanuel, but I'm not so sure of that. There's always been more love on his side than on her side, from the beginning, by the time he truly approaches her and opens up to her, she's been despairing, feeling pain for her unrequited love, coping with lonesomeness and questioning the chance of happiness- who knows if she loves him because of his personality and character, or does so as a lonely person that wants attachment.

Who knows.

Pages

▼

Friday, 26 September 2014

Thursday, 25 September 2014

William Faulkner on the human dilemma

... You’re alive in the world. You see man. You have an insatiable curiosity about him, but more than that you have an admiration for him. He is frail and fragile, a web of flesh and bone and mostly water. He’s flung willy nilly into a ramshackle universe stuck together with electricity. The problems he faces are always a little bigger than he is, and yet, amazingly enough, he copes with them — not individually but as a race.

He endures.

He’s outlasted dinosaurs. He’s outlasted atom bombs. He’ll outlast communism. Simply because there’s some part in him that keeps him from ever knowing that he’s whipped, I suppose; that as frail as he is, he lives up to his codes of behavior. He shows compassion when there’s no reason why he should. He’s braver than he should be. He’s more honest.

The writer is so interested — he sees this as so amazing and you might say so beautiful… It’s so moving to him that he wants to put it down on paper or in music or on canvas, that he simply wants to isolate one of these instances in which man — frail, foolish man — has acted miles above his head in some amusing or dramatic or tragic way… some gallant way.

That, I suppose, is the incentive to write, apart from it being fun. I sort of believe that is the reason that people are artists. It’s the most satisfying occupation man has discovered yet, because you never can quite do it as well as you want to, so there’s always something to wake up tomorrow morning to do. You’re never bored. You never reach satiation.

(William Faulkner, http://www.brainpickings.org/2014/09/25/william-faulkner-university-of-virginia-recording/?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+brainpickings%2Frss+%28Brain+Pickings%29)

My reception of Villette

is something like this:

*

*

Please don't think that the last point is my last thought on Villette- I haven't finished reading the book. It's only my state of mind right now, a few scenes after the unfolding of Paul Emanuel's hidden side, the self-sacrificing, saintly (/Christian) side. This is a good, realistic character, 1 of Charlotte Bronte's best, and everything was going very, very well until the revelation scene- improbable and unconvincing and... I don't even have the word.

Still, the good news is that the general trend is still going up and up and up, so there is chance that it will go up again soon.

Oh Charlotte Charlotte Charlotte.

*: And don't take that graph too seriously.

*

*Please don't think that the last point is my last thought on Villette- I haven't finished reading the book. It's only my state of mind right now, a few scenes after the unfolding of Paul Emanuel's hidden side, the self-sacrificing, saintly (/Christian) side. This is a good, realistic character, 1 of Charlotte Bronte's best, and everything was going very, very well until the revelation scene- improbable and unconvincing and... I don't even have the word.

Still, the good news is that the general trend is still going up and up and up, so there is chance that it will go up again soon.

Oh Charlotte Charlotte Charlotte.

*: And don't take that graph too seriously.

Monday, 22 September 2014

Notes from "The Economic Determinants of Democracy and Dictatorship"

Chapter 6 of Principles of Comparative Politics (William Roberts Clark, Matt Golder and Sona Nadenichek Golder)+ some extra essays.

- Income and democracy are correlated.

- "Classic modernisation theory argues that countries are more likely both to become democratic and to stay democratic as they develop economically."

- Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, "Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution":

Examines the reversal of fortune- why some countries were very rich before and poor now, and vice versa. Finds that a) it's linked to colonialism (extractive institutions in previously rich, crowded areas and institutions of private property in previously poor, sparsely populated areas) and b) the geography hypothesis (geographic, climatic, ecological factors) is wrong, the most important factors are economic and political institutions.

We see rich and democratic countries, and poor and autocratic countries, but that doesn't necessarily mean a causal relationship, but rather that they both result from the same thing- institutions.

- Various views:

+ Lipset:

For modernisation theory.

Extremism and polarisation are factors that work against democracy.

Education mitigates extremism.

Industrialisation and urbanisation help society open up for different influences=> tolerance and broad-mindedness.

Economic inequality and poverty lead to social conflicts and antagonism between the classes.

The middle class in a modern society is a moderating influence that works in favour of democracy.

When a country's richer, it has larger chances to sustain democracy.

(Criticism: Different paths to modernity.

Authoritarianism in rich, industrialised countries.

The middle class's fear of industrial workers' power may make them want to call for a strong hand).

Rapid growth's bad for democracy.

+ Przeworski and Limongi, "Modernization: Theory and Facts":

Against modernisation theory (endogenous view).

Instead, survival theory: economic development helps survival (exogenous view) but doesn't cause democratisation.

Simple explanation for survival theory: in a democracy, you all get a share; in a dictatorship, you win everything or lose everything. If you're rich in a democracy, you'd like to stay in a democracy, because even though you have a chance to be richer, there's also a possibility of losing everything. If you're poor, there's nothing to fear, and you have a chance to become rich when switching to a dictatorship.

Growth isn't destabilising for democracy. Crisis is, but only for poor democracies. But it's destabilising for dictatorships, both rich and poor.

+ Boix and Stokes, "Endogenous Democratization":

Criticises Przeworski's and Limongi's use of data.

Omits Soviet countries (USSR pressure) and oil countries. The tables show that economic development both sustains and causes democracy.

+ Kennedy, "The Contradiction of Modernization: A Conditional Model of Endogenous Democratization":

Higher income reduces probability of change and stabilises all kinds of regimes, but if a change takes place then the richer a country, the higher chances it ends in democracy.

High short-term growth=> low probability of democratisation.

+ A variant of modernisation theory:

It isn't income per se that encourages democratisation but rather the institutional changes that accompany economic development.

Incorporates the predatory view of the state.

Linked to the commitment problem. People are unwilling to give loans to the state if there's no guarantee that the state will pay back the money, and this may do harm to the economy unless there are institutional changes- this is often said to "explain the institutional reforms that led to the establishment of modern parliamentary democracy in Britain during the Glorious Revolution".

Note the concept of quasi-rent, which is the difference between an asset's value and its short-run opportunity cost. There are 2 kinds of asset: A fixed asset, such as a copper mine, has large quasi-rents because if it doesn't produce copper, there isn't much you can do with it, which means that fixed asset holders don't have credible exit options, therefore the state can choose to be unresponsive. A liquid asset is flexible (can be turned into other types of assets), the state depends on liquid asset holders for investment and resources and is more likely to accept limits on their predatory behaviour. This explains the resource curse- countries that are abundant in natural resources, such as oil, tend to be dictatorships, though there are also other factors (revenue from natural resources allows the state to buy off citizens by lowering taxation, reward the military, use control over national companies such as oil companies to hide its finances, etc).

- North and Weingast, "Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institution Governing Public Choice in 17th Century England":

Fearing of not getting loans in the future doesn't necessarily prevent reneging. Consider the time of war, survival is at stake and the sovereign would discount the future.

The role of the Bank of England.

"Successful economic performance [...] must be accompanied by institutions that limit economic intervention and allow private rights and markets to prevail in large segments of the economy".

The commitment by the government to honour its financial agreement is part of a larger commitment to secure private rights.

- Providing foreign aid for dictatorships may inhibit the emergence of democracy, help dictators hold onto power and prolong the suffering the people because it reduces the dependence of the state on the citizens as well as the incentive to have good economic performance.

- Inequality (these theories draw on the premise that democracy's expected to cause/increase redistribution):

+ Boix and Stokes:

Inequality harms both democratisation and consolidation.

Increased income=> reduced inequality=> democratisation (this is, of course, debatable).

Low inequality=> the elites have less to lose and don't want to risk revolution=> they democratise.

Unequal authoritarian regimes are less likely to become democratic because the elites fear redistribution (the lower classes can't credibly promise to tax lightly when they gain power).

+ Acemoglu and Robinson:

Inequality inhibits consolidation but relates to democratisation through an inverted U-shaped curve:

+ Houle, "Inequality and Democracy":

2 opposite effects: on the 1 hand, inequality makes democracy costly for the elites, who fear redistribution; on the other hand, inequality increases people's demand for regime change.

Acemoglu and Robinson forget a) all authoritarian regimes require some repression, b) revolts aren't equally costly and c) inequality doesn't necessarily lead to revolts because people may fear imprisonment or death, therefore "the elites have no incentive to respond to changes in inequality by adopting democracy".

The 2 transitions processes (democracy=> dictatorship, dictatorship=> democracy) are asymmetric.

Egalitarian democracies are more stable: low inequality=> less to gain for the elites from conducting a coup.

Inequality harms consolidation but doesn't affect democratisation (no empirical evidence).

=> Conclusion:

Short-term growth and oil=> good for survival of authoritarian regimes.

Income level?=> depends.

- Income and democracy are correlated.

- "Classic modernisation theory argues that countries are more likely both to become democratic and to stay democratic as they develop economically."

- Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, "Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution":

Examines the reversal of fortune- why some countries were very rich before and poor now, and vice versa. Finds that a) it's linked to colonialism (extractive institutions in previously rich, crowded areas and institutions of private property in previously poor, sparsely populated areas) and b) the geography hypothesis (geographic, climatic, ecological factors) is wrong, the most important factors are economic and political institutions.

We see rich and democratic countries, and poor and autocratic countries, but that doesn't necessarily mean a causal relationship, but rather that they both result from the same thing- institutions.

- Various views:

+ Lipset:

For modernisation theory.

Extremism and polarisation are factors that work against democracy.

Education mitigates extremism.

Industrialisation and urbanisation help society open up for different influences=> tolerance and broad-mindedness.

Economic inequality and poverty lead to social conflicts and antagonism between the classes.

The middle class in a modern society is a moderating influence that works in favour of democracy.

When a country's richer, it has larger chances to sustain democracy.

(Criticism: Different paths to modernity.

Authoritarianism in rich, industrialised countries.

The middle class's fear of industrial workers' power may make them want to call for a strong hand).

Rapid growth's bad for democracy.

+ Przeworski and Limongi, "Modernization: Theory and Facts":

Against modernisation theory (endogenous view).

Instead, survival theory: economic development helps survival (exogenous view) but doesn't cause democratisation.

Simple explanation for survival theory: in a democracy, you all get a share; in a dictatorship, you win everything or lose everything. If you're rich in a democracy, you'd like to stay in a democracy, because even though you have a chance to be richer, there's also a possibility of losing everything. If you're poor, there's nothing to fear, and you have a chance to become rich when switching to a dictatorship.

Growth isn't destabilising for democracy. Crisis is, but only for poor democracies. But it's destabilising for dictatorships, both rich and poor.

+ Boix and Stokes, "Endogenous Democratization":

Criticises Przeworski's and Limongi's use of data.

Omits Soviet countries (USSR pressure) and oil countries. The tables show that economic development both sustains and causes democracy.

+ Kennedy, "The Contradiction of Modernization: A Conditional Model of Endogenous Democratization":

Higher income reduces probability of change and stabilises all kinds of regimes, but if a change takes place then the richer a country, the higher chances it ends in democracy.

High short-term growth=> low probability of democratisation.

+ A variant of modernisation theory:

It isn't income per se that encourages democratisation but rather the institutional changes that accompany economic development.

Incorporates the predatory view of the state.

Linked to the commitment problem. People are unwilling to give loans to the state if there's no guarantee that the state will pay back the money, and this may do harm to the economy unless there are institutional changes- this is often said to "explain the institutional reforms that led to the establishment of modern parliamentary democracy in Britain during the Glorious Revolution".

Note the concept of quasi-rent, which is the difference between an asset's value and its short-run opportunity cost. There are 2 kinds of asset: A fixed asset, such as a copper mine, has large quasi-rents because if it doesn't produce copper, there isn't much you can do with it, which means that fixed asset holders don't have credible exit options, therefore the state can choose to be unresponsive. A liquid asset is flexible (can be turned into other types of assets), the state depends on liquid asset holders for investment and resources and is more likely to accept limits on their predatory behaviour. This explains the resource curse- countries that are abundant in natural resources, such as oil, tend to be dictatorships, though there are also other factors (revenue from natural resources allows the state to buy off citizens by lowering taxation, reward the military, use control over national companies such as oil companies to hide its finances, etc).

- North and Weingast, "Constitutions and Commitment: The Evolution of Institution Governing Public Choice in 17th Century England":

Fearing of not getting loans in the future doesn't necessarily prevent reneging. Consider the time of war, survival is at stake and the sovereign would discount the future.

The role of the Bank of England.

"Successful economic performance [...] must be accompanied by institutions that limit economic intervention and allow private rights and markets to prevail in large segments of the economy".

The commitment by the government to honour its financial agreement is part of a larger commitment to secure private rights.

- Providing foreign aid for dictatorships may inhibit the emergence of democracy, help dictators hold onto power and prolong the suffering the people because it reduces the dependence of the state on the citizens as well as the incentive to have good economic performance.

- Inequality (these theories draw on the premise that democracy's expected to cause/increase redistribution):

+ Boix and Stokes:

Inequality harms both democratisation and consolidation.

Increased income=> reduced inequality=> democratisation (this is, of course, debatable).

Low inequality=> the elites have less to lose and don't want to risk revolution=> they democratise.

Unequal authoritarian regimes are less likely to become democratic because the elites fear redistribution (the lower classes can't credibly promise to tax lightly when they gain power).

+ Acemoglu and Robinson:

Inequality inhibits consolidation but relates to democratisation through an inverted U-shaped curve:

- Low inequality=> the elites can commit to redistribution (less costly)=> the lower classes have less incentive to fight for a regime change.

- Intermediate level of inequality=> redistribution is relatively inexpensive (they do have much to lose, but revolution and Marxist regime are worse) => the elites are unwilling to use repression=> they democratise.

- Higher level of inequality=> the cost of redistribution surpasses that of repressing revolts=> the elites repress the population=> no democratisation.

+ Houle, "Inequality and Democracy":

2 opposite effects: on the 1 hand, inequality makes democracy costly for the elites, who fear redistribution; on the other hand, inequality increases people's demand for regime change.

Acemoglu and Robinson forget a) all authoritarian regimes require some repression, b) revolts aren't equally costly and c) inequality doesn't necessarily lead to revolts because people may fear imprisonment or death, therefore "the elites have no incentive to respond to changes in inequality by adopting democracy".

The 2 transitions processes (democracy=> dictatorship, dictatorship=> democracy) are asymmetric.

Egalitarian democracies are more stable: low inequality=> less to gain for the elites from conducting a coup.

Inequality harms consolidation but doesn't affect democratisation (no empirical evidence).

=> Conclusion:

Short-term growth and oil=> good for survival of authoritarian regimes.

Income level?=> depends.

Contradictory attributes of character

"What contradictory attributes of character we sometimes find ascribed to us, according to the eye with which we are viewed! Madame Beck esteemed me learned and blue; Miss Fanshaw, caustic, ironic, and cynical; Mr Home, a model teacher, the essence of the sedate and discreet: somewhat conventional, perhaps, too strict, limited and scrupulous, but still the pink and pattern of governess-correctness; whilst another person, Professor Paul Emanuel to wit, never lost an opportunity of intimating his opinion that mine was rather a fiery and rash nature- adventurous, indocile, and audacious. I smiled at them all. If anyone knew me it was little Paulina Mary."

(Villette)

(Villette)

Sunday, 21 September 2014

On the Waterfront

Just watched On the Waterfront.

I'm too overwhelmed to write anything. What can top this Elia Kazan- Marlon Brando collaboration? Perhaps only the masterpiece that combines the genius of Elia Kazan, Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh.

I'm too overwhelmed to write anything. What can top this Elia Kazan- Marlon Brando collaboration? Perhaps only the masterpiece that combines the genius of Elia Kazan, Marlon Brando and Vivien Leigh.

Saturday, 20 September 2014

The Bronte sisters and stylometric analysis

http://alanabeeblog.wordpress.com/2013/11/11/computational-stylistics-and-the-bronte-sisters/

http://alanabeeblog.wordpress.com/2013/12/19/the-bronte-sisters-a-stylometric-analysis/

You can click the 2 links above to read the whole thing.

Cluster analysis when there are only books by the Brontes:

(http://alanabeeblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/brontecluster.png)

When some works by Jane Austen and George Eliot are added:

(http://alanabeeblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/bronte2.png)

(http://alanabeeblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/bronteconsen2.png)

Charlotte, Emily and Anne are, to me, distinctive, but now according to this analysis, they appear like a single author. Not sure if it's reliable, but this is interesting.

http://alanabeeblog.wordpress.com/2013/12/19/the-bronte-sisters-a-stylometric-analysis/

You can click the 2 links above to read the whole thing.

Cluster analysis when there are only books by the Brontes:

(http://alanabeeblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/brontecluster.png)

When some works by Jane Austen and George Eliot are added:

(http://alanabeeblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/bronte2.png)

(http://alanabeeblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/bronteconsen2.png)

Charlotte, Emily and Anne are, to me, distinctive, but now according to this analysis, they appear like a single author. Not sure if it's reliable, but this is interesting.

Reading Villette, thinking of Charlotte Bronte and Jane Austen

Reading Villette.

Charlotte Bronte is not Jane Austen (can anyone talk about 19th century British literature, or women's literature, without at some point bringing up Jane Austen?- at least I can't). This can be both a bad thing and a good thing.

Bad: she is inferior as an artist. She lacks experience and doesn't have a sharp eye for character, and doesn't have Jane Austen's serenity and cool detachment- like Virginia Woolf has noted, Charlotte lets her indignation distort her art. More importantly, she's extremely bad with plot. Like Jane Eyre, the plot of Villette is contrived, full of implausibilities (there's no way one can read Villette without knowing that it's by the author of Jane Eyre). For instance, Lucy Snowe arrives in Villette, hoping to find Madame Beck, which doesn't seem easy because this is a city in a new country Lucy has never visited, and she doesn't know where the woman lives. However, whilst trying to find her trunk, Lucy meets and gets help from an Englishman, then asks him about an inn where she can stay for the night. He gives her the address of a place, which turns out to be Madame Beck's place. The man helping Lucy works there and is known as Dr John. A while later, during the holiday, Lucy gets sick, faints and is saved by Dr John, who turns out to be Graham, the son of Lucy's godmother in England, introduced in the 1st chapters.

Or, on a ship Lucy gets acquainted with a girl named Ginevra Fanshawe and, not knowing where to go, decides to come to Villette and find a job at Madame Beck's school, where Ginevra studies. Then it turns out that 1 of Ginevra's 2 suitors, codenamed Isidore, is John, aka Graham. Well that's OK. But later in the story, there's a scene when Graham and Lucy go to the theatre and he helps a girl, who is afterwards said to be Ginevra's cousin and who, as I guessed correctly, is later revealed to be Polly, the little girl who stays at Mrs Bretton with Graham and Lucy at the beginning of the story.

Such contrived, unnatural, unconvincing bits can be like little itches, seemingly insignificant but irritating nevertheless. Reading fiction, we know that everything's in the author's imagination, but still feel bothered when noticing the author's hand moving around in the story, touching this, moving that, instead of giving the illusion that everything happens naturally and follows their own course. Another detail is that, at the beginning of the story, the narrator doesn't speak French yet still can write down other characters' speech in French. The author clearly isn't very careful.

However, I shouldn't be unfair to Charlotte Bronte. It's a good thing too that she's not Jane Austen. She has the imagination, the power and intensity and boldness not found in Jane Austen (Charlotte's books are too exciting and imaginative to be read slowly). I've compared Jane Eyre and Fanny Price once- they are similar in many aspects, but Jane Eyre can do many things Fanny is never capable of. More importantly, in Charlotte, we find a yearning for something greater, a refusal to stay within bounds. She is never prosaic or mundane. She is poetic. Reading her books, one feels at one with nature. Reading her books, one is transferred to a different world. And she writes not to teach- Jane Austen never preaches, but still wants to teach or to make a point about virtue and balance, Charlotte Bronte doesn't do so. It's all about imagination and emotions. Not as cold and detached as Jane Austen, she is more personal and thus touches us deeply and moves us strongly.

And that is sometimes a lot more important than artistic perfection.

Charlotte Bronte is not Jane Austen (can anyone talk about 19th century British literature, or women's literature, without at some point bringing up Jane Austen?- at least I can't). This can be both a bad thing and a good thing.

Bad: she is inferior as an artist. She lacks experience and doesn't have a sharp eye for character, and doesn't have Jane Austen's serenity and cool detachment- like Virginia Woolf has noted, Charlotte lets her indignation distort her art. More importantly, she's extremely bad with plot. Like Jane Eyre, the plot of Villette is contrived, full of implausibilities (there's no way one can read Villette without knowing that it's by the author of Jane Eyre). For instance, Lucy Snowe arrives in Villette, hoping to find Madame Beck, which doesn't seem easy because this is a city in a new country Lucy has never visited, and she doesn't know where the woman lives. However, whilst trying to find her trunk, Lucy meets and gets help from an Englishman, then asks him about an inn where she can stay for the night. He gives her the address of a place, which turns out to be Madame Beck's place. The man helping Lucy works there and is known as Dr John. A while later, during the holiday, Lucy gets sick, faints and is saved by Dr John, who turns out to be Graham, the son of Lucy's godmother in England, introduced in the 1st chapters.

Or, on a ship Lucy gets acquainted with a girl named Ginevra Fanshawe and, not knowing where to go, decides to come to Villette and find a job at Madame Beck's school, where Ginevra studies. Then it turns out that 1 of Ginevra's 2 suitors, codenamed Isidore, is John, aka Graham. Well that's OK. But later in the story, there's a scene when Graham and Lucy go to the theatre and he helps a girl, who is afterwards said to be Ginevra's cousin and who, as I guessed correctly, is later revealed to be Polly, the little girl who stays at Mrs Bretton with Graham and Lucy at the beginning of the story.

Such contrived, unnatural, unconvincing bits can be like little itches, seemingly insignificant but irritating nevertheless. Reading fiction, we know that everything's in the author's imagination, but still feel bothered when noticing the author's hand moving around in the story, touching this, moving that, instead of giving the illusion that everything happens naturally and follows their own course. Another detail is that, at the beginning of the story, the narrator doesn't speak French yet still can write down other characters' speech in French. The author clearly isn't very careful.

However, I shouldn't be unfair to Charlotte Bronte. It's a good thing too that she's not Jane Austen. She has the imagination, the power and intensity and boldness not found in Jane Austen (Charlotte's books are too exciting and imaginative to be read slowly). I've compared Jane Eyre and Fanny Price once- they are similar in many aspects, but Jane Eyre can do many things Fanny is never capable of. More importantly, in Charlotte, we find a yearning for something greater, a refusal to stay within bounds. She is never prosaic or mundane. She is poetic. Reading her books, one feels at one with nature. Reading her books, one is transferred to a different world. And she writes not to teach- Jane Austen never preaches, but still wants to teach or to make a point about virtue and balance, Charlotte Bronte doesn't do so. It's all about imagination and emotions. Not as cold and detached as Jane Austen, she is more personal and thus touches us deeply and moves us strongly.

And that is sometimes a lot more important than artistic perfection.

Thursday, 11 September 2014

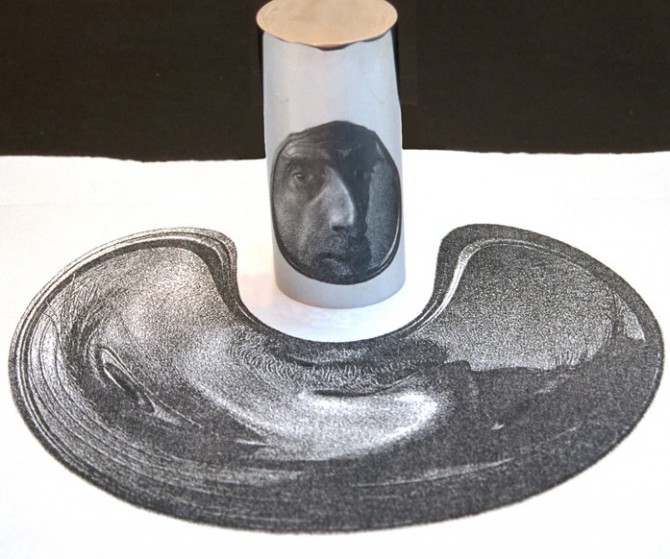

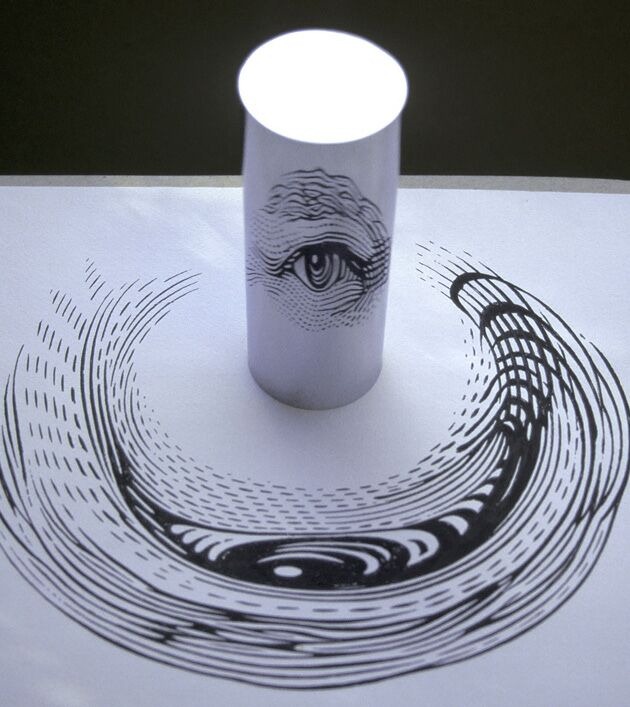

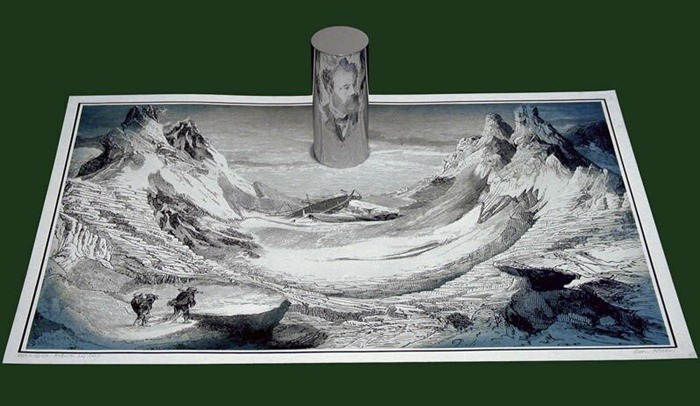

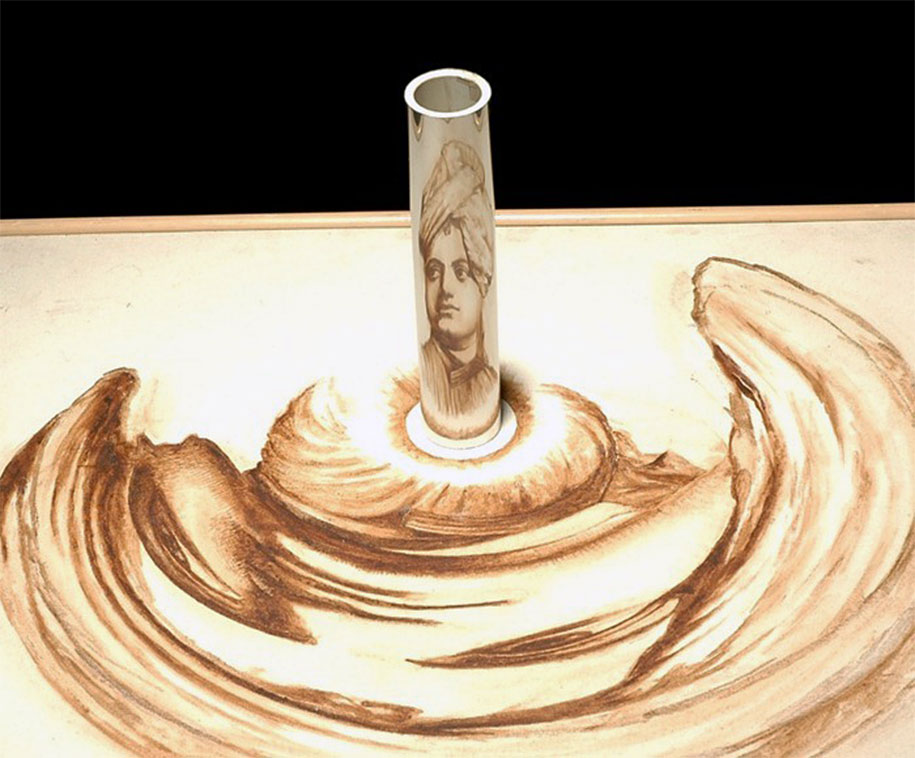

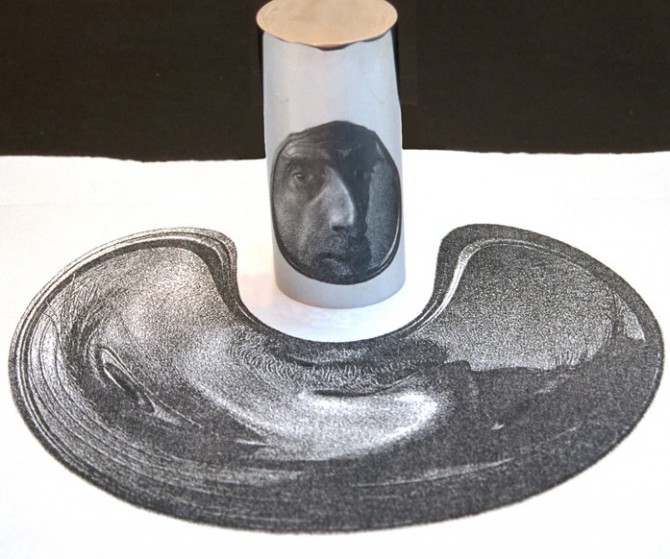

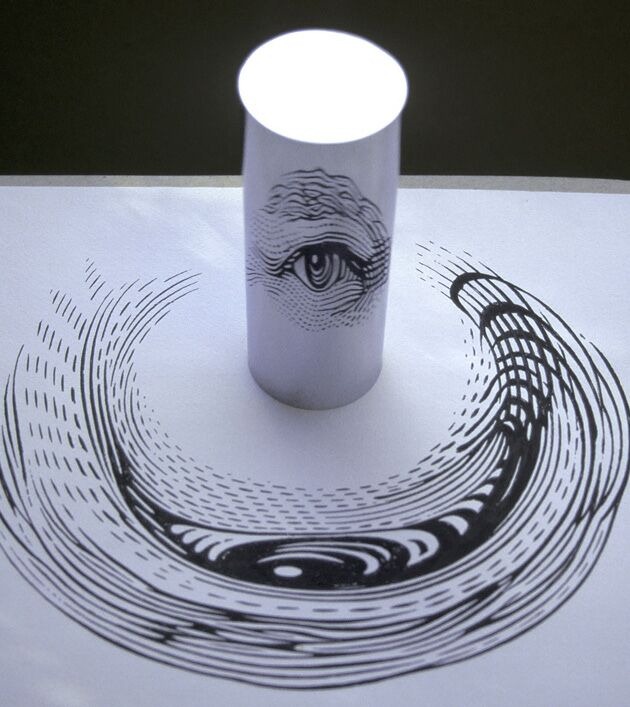

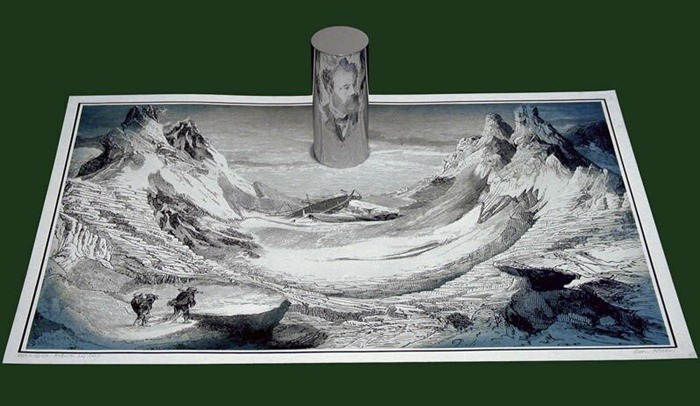

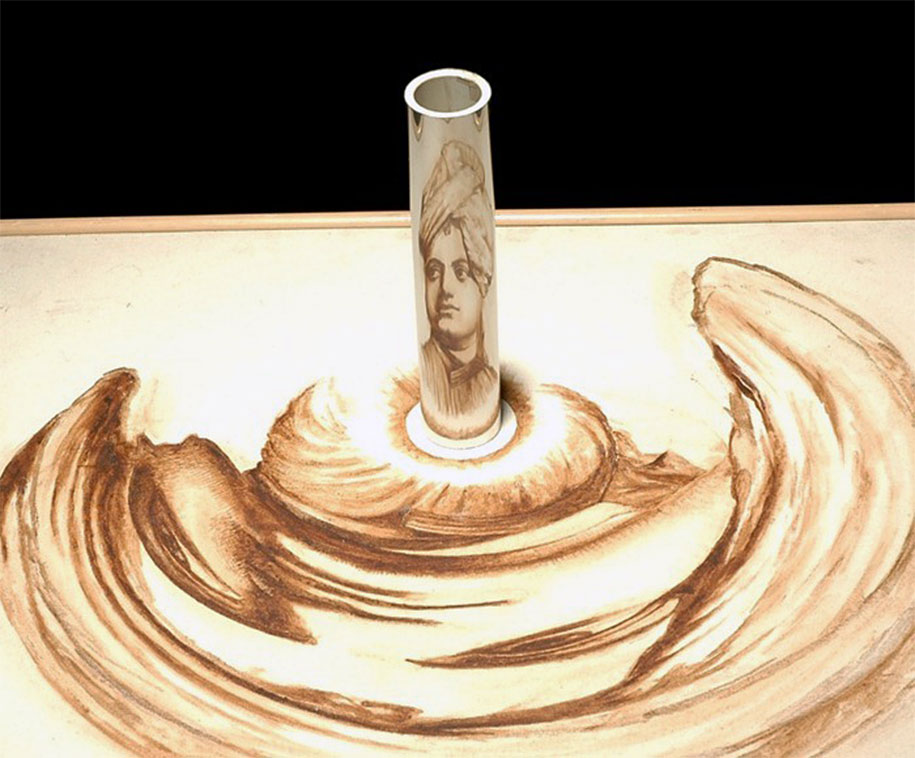

Anamorphic artworks by István Orosz and some others

By István Orosz:

By Jonty Hurwitz:

By Rex Young:

By William Kentridge:

By Awtar Singh Virdi:

From http://imgur.com/HfJyR9d:

From facebook.com/artpeople1, amusingplanet.com, demilked.com and some other sites.

By Jonty Hurwitz:

By Rex Young:

By William Kentridge:

By Awtar Singh Virdi:

From http://imgur.com/HfJyR9d:

From facebook.com/artpeople1, amusingplanet.com, demilked.com and some other sites.

Adapting Jane Austen

A no-nonsense article on how film adaptations completely misunderstand Jane Austen:

"Finally! The teenage passion of Jane Austen will become known to the world! Chemistry! Passion! Rebellious self-determination! With the movie Becoming Jane, devoted fans will become ever more devoted! The Regency period and the twenty-first century will embrace!

[...]

An obscene 1999 film (in which, among other things, Sir Thomas Bertram abuses and rapes slaves, Miss Crawford makes sexual advances on every other character and a few pieces of furniture, and Fanny happens upon her cousin Maria and Mr. Crawford in flagrante delicto) and a more traditional 2007 ITV production have both tried to reinvent the heroine altogether, rejecting her modesty, timidity, physical frailty, and staunch sincerity in favor of an unlikely, outspoken, and altogether too-hardy specimen of proto-feminism.

In the novel, Fanny is quiet, Fanny endures, and Fanny is essentially good. It requires the full length of the novel for her to be esteemed by her fellow characters and rewarded as she deserves; it may take several more decades for modern readers (or viewers) to attain such clarity.

As the cinematic treatment of this novel shows, instead of embracing the depth of feeling of the novels, and Miss Austen’s characteristically deft articulation of the authentic human experience, modern readers tend to reject or misinterpret what they cannot bear to acknowledge: the fact that virtue, not force of will, is the basis for heroism in Austen’s world.

[...]

The heroines of Jane Austen are not the selfish, willful, reckless creatures who sow social disruption and pain in their wake. They are the eager and essentially virtuous maidens who, although they often make mistakes, have a well-established code of virtuous behavior and can recover from any misstep..."

______________________________________________

My thoughts:

1/ The 1999 Mansfield Park film is a betrayal of the book.

a) Fanny is an outsider, a Cinderella figure, who feels that she doesn't belong to Mansfield park throughout most of the story. She grows up in the little white attic, close to nobody but Edmund. Her personality is introverted, introspective, the situation makes her more timid and modest, especially when there's always a Mrs Norris to remind her of who she is. The Fanny of the film, even if we forget the book, is too outspoken for a girl under such circumstances.

b) Nothing is as distasteful as associating Jane Austen with 1 of her heroines. Why bring details of Jane Austen's life into the characterisation of Fanny?

c) Fanny in the film says yes to Henry- of course, the next day she takes it back (as Jane Austen did once in real life), but saying yes once already betrays the stance and the spirit of the book.

In Jane Austen's novel, Fanny's outward frailty is contrasted with her inner strength, her firmness and strong principle, she refuses Henry less because of her hopeless love for Edmund than because of her distrusting of Henry, based on his character. The film fails to grasp that. It should be fine if they want to borrow the story, change it, add their own ideas to it, but with these changes, the Mansfield Park film becomes rather pointless.

Fortunately, much as I hated the film (and still do), it didn't put me off the novel.

(Must tell myself: Never judge a book by its movie).

2/ Why do filmmakers think that they must add some water to Darcy to make women adore him? Isn't Darcy of the book enough?

In the 1995 TV film, Colin Firth's Darcy swims in the lake and comes out wet and encounters Elizabeth.

In the 2005 film, Matthew Macfadyen's Darcy proposes to Elizabeth (the 1st time) in the rain.

I suspect that many people who say they adore Jane Austen in fact only adore Pride and Prejudice, swoon over the charming Colin Firth and imagine themselves as Elizabeth Bennet.

3/ On principle, no.2 should not matter.

But a few days ago, below an article on http://thedissolve.com about Emma and Clueless, I saw this comment:

4/ I watched only part of Becoming Jane. Much as I like Anne Hathaway, I couldn't continue watching.

Her bad accent is 1 thing, I don't like the way the film presents Jane Austen as Elizabeth Bennet, and suggests that she incorporated her personal experience into her novel. It's distasteful (go back to 1b). Besides, in popular culture, the name Jane Austen almost always goes with Pride and Prejudice, though Mansfield Park, Emma and Persuasion are artistically greater and deeper and Mansfield Park is her most complex and profound work.

5/ I dislike the tendency of many film adaptations to romanticise literary works.

A sentimental Jane Austen film is very, very wrong. Worse is the case of Wuthering Heights- many films remove the 2nd part about the later generation and focus on the love story between Catherine and Heathcliff, but Emily Bronte's book is not about a beautiful love story- it's about greed, the love vs money/ social position question, about obsession and hatred and revenge...

Or think of the latest The Great Gatsby film. Baz Luhrmann strips Fitzgerald's story of all the essential things and of the main theme, the result is no more than a love story, visually dazzling but empty.

6/ However, you should not have the mistaken view that I dislike all of the adaptations. Nor should you think that I always demand adaptations to be faithful- an adaptation is an interpretation and the filmmaker can take liberties with a story, as long as the film is good, I wouldn't object.

1 good film I can think of is Ang Lee's Sense and Sensibility. Emma Thompson's script creates greater contrast between Elinor and Marianne (unlike the 2008 TV adaptation), and if Jane Austen's more on the side of sense (Elinor), Emma Thompson's a bit more on the side of sensibility (Marianne). I do not think that Jane Austen thinks of Elinor as perfect and ideal, the story simply tends to be seen from her point of view; Elinor doesn't express her emotions so on the 1 hand, Edward never knows how she feels and doesn't know how to act and Elinor almost loses her chance of happiness, on the other hand, she has an outburst in the end after holding back emotions for a long time. Think of Jane Fairfax in Emma, she's too reserved and, as George Knightley notes (which I think is also Jane Austen's opinion), an open temper is preferable; similarly, Elinor's too reserved. Other characters remain the same, the mercenary, greedy... people are still in the story. In short, the 1995 Sense and Sensibility offers a new interpretation without betraying Jane Austen's general idea about the balance of sense and sensibility (one can see from the works that her emphasis is on virtue, good will and balance).

Another film is Clueless, a modernisation of Emma. Let me digress a bit: one may wonder how Jane Austen can sympathise with all of her heroines, different as they are, but what they have in common is that, whatever faults they have, they always mean well (unlike Mary Crawford, albeit similar to Elizabeth on the surface because of her charm and vivacity, is egoistic, insensitive, frivolous, shallow, insincere, manipulative, mercenary... and should be in the same camp with Lucy Steele, Caroline Bingley, Susan Vernon, Fanny Dashwood...). Emma Woodhouse is not as likeable as Elizabeth Bennet; anyone adapting Emma faces the danger of depicting Emma as full of malice and contempt. Clueless doesn't do that- like Emma, Cher makes mistakes because she interferes in other people's lives, thinking she knows all, but is in fact delusional, but she means well; like Emma, Cher is good-natured and capable of learning and changing in the end. Clueless modernises the story, changes the setting, changes a few characters and details, but the spirit is the same. And it's well-done.

a) Fanny is an outsider, a Cinderella figure, who feels that she doesn't belong to Mansfield park throughout most of the story. She grows up in the little white attic, close to nobody but Edmund. Her personality is introverted, introspective, the situation makes her more timid and modest, especially when there's always a Mrs Norris to remind her of who she is. The Fanny of the film, even if we forget the book, is too outspoken for a girl under such circumstances.

b) Nothing is as distasteful as associating Jane Austen with 1 of her heroines. Why bring details of Jane Austen's life into the characterisation of Fanny?

c) Fanny in the film says yes to Henry- of course, the next day she takes it back (as Jane Austen did once in real life), but saying yes once already betrays the stance and the spirit of the book.

In Jane Austen's novel, Fanny's outward frailty is contrasted with her inner strength, her firmness and strong principle, she refuses Henry less because of her hopeless love for Edmund than because of her distrusting of Henry, based on his character. The film fails to grasp that. It should be fine if they want to borrow the story, change it, add their own ideas to it, but with these changes, the Mansfield Park film becomes rather pointless.

Fortunately, much as I hated the film (and still do), it didn't put me off the novel.

(Must tell myself: Never judge a book by its movie).

2/ Why do filmmakers think that they must add some water to Darcy to make women adore him? Isn't Darcy of the book enough?

In the 1995 TV film, Colin Firth's Darcy swims in the lake and comes out wet and encounters Elizabeth.

In the 2005 film, Matthew Macfadyen's Darcy proposes to Elizabeth (the 1st time) in the rain.

I suspect that many people who say they adore Jane Austen in fact only adore Pride and Prejudice, swoon over the charming Colin Firth and imagine themselves as Elizabeth Bennet.

3/ On principle, no.2 should not matter.

But a few days ago, below an article on http://thedissolve.com about Emma and Clueless, I saw this comment:

"Fanny decides to marry the Mr. Collins character (who is also her first cousin) instead of the Mr. Darcy character (who is played by Alessandro Nivola in the movie, at his peak Alessandro Nivola-ness). Then said rejected charming/handsome suitor has sex with her married cousin Mariah and everyone reacts as they would in 1814: "Well, we can never talk to either of them again! Cross her name out of the family Bible!""I don't usually voice my opinion, but whenever it comes to Mansfield Park.... So I had to write:

"Hold on... Darcy?

For 1 thing, Henry is a bad guy, vain, selfish, insensitive, deceitful and unreliable, who toys with women's feelings. I don't see any similarities between him and Darcy. The problem is not simply that Henry sleeps, or elopes, with Maria; but his character in general, he toys with women's feelings, flirts with many women at the same time without caring about how they feel.

Besides, I have never seen Darcy as a particularly charming guy. In fact, he's even rude. The word "charming" would apply for Henry Crawford, William Elliot or Willoughby, and among Jane Austen's good guys, I think the only one that can be called charming (to me anyway) is Henry Tilney. You must have Colin Firth in mind. Readers of Pride and Prejudice like him not because he's charming, but because he's generous, sincere, understanding (especially in the way he handles the Wickham- Lydia business).

I don't think you've really read the books."

4/ I watched only part of Becoming Jane. Much as I like Anne Hathaway, I couldn't continue watching.

Her bad accent is 1 thing, I don't like the way the film presents Jane Austen as Elizabeth Bennet, and suggests that she incorporated her personal experience into her novel. It's distasteful (go back to 1b). Besides, in popular culture, the name Jane Austen almost always goes with Pride and Prejudice, though Mansfield Park, Emma and Persuasion are artistically greater and deeper and Mansfield Park is her most complex and profound work.

5/ I dislike the tendency of many film adaptations to romanticise literary works.

A sentimental Jane Austen film is very, very wrong. Worse is the case of Wuthering Heights- many films remove the 2nd part about the later generation and focus on the love story between Catherine and Heathcliff, but Emily Bronte's book is not about a beautiful love story- it's about greed, the love vs money/ social position question, about obsession and hatred and revenge...

Or think of the latest The Great Gatsby film. Baz Luhrmann strips Fitzgerald's story of all the essential things and of the main theme, the result is no more than a love story, visually dazzling but empty.

6/ However, you should not have the mistaken view that I dislike all of the adaptations. Nor should you think that I always demand adaptations to be faithful- an adaptation is an interpretation and the filmmaker can take liberties with a story, as long as the film is good, I wouldn't object.

1 good film I can think of is Ang Lee's Sense and Sensibility. Emma Thompson's script creates greater contrast between Elinor and Marianne (unlike the 2008 TV adaptation), and if Jane Austen's more on the side of sense (Elinor), Emma Thompson's a bit more on the side of sensibility (Marianne). I do not think that Jane Austen thinks of Elinor as perfect and ideal, the story simply tends to be seen from her point of view; Elinor doesn't express her emotions so on the 1 hand, Edward never knows how she feels and doesn't know how to act and Elinor almost loses her chance of happiness, on the other hand, she has an outburst in the end after holding back emotions for a long time. Think of Jane Fairfax in Emma, she's too reserved and, as George Knightley notes (which I think is also Jane Austen's opinion), an open temper is preferable; similarly, Elinor's too reserved. Other characters remain the same, the mercenary, greedy... people are still in the story. In short, the 1995 Sense and Sensibility offers a new interpretation without betraying Jane Austen's general idea about the balance of sense and sensibility (one can see from the works that her emphasis is on virtue, good will and balance).

Another film is Clueless, a modernisation of Emma. Let me digress a bit: one may wonder how Jane Austen can sympathise with all of her heroines, different as they are, but what they have in common is that, whatever faults they have, they always mean well (unlike Mary Crawford, albeit similar to Elizabeth on the surface because of her charm and vivacity, is egoistic, insensitive, frivolous, shallow, insincere, manipulative, mercenary... and should be in the same camp with Lucy Steele, Caroline Bingley, Susan Vernon, Fanny Dashwood...). Emma Woodhouse is not as likeable as Elizabeth Bennet; anyone adapting Emma faces the danger of depicting Emma as full of malice and contempt. Clueless doesn't do that- like Emma, Cher makes mistakes because she interferes in other people's lives, thinking she knows all, but is in fact delusional, but she means well; like Emma, Cher is good-natured and capable of learning and changing in the end. Clueless modernises the story, changes the setting, changes a few characters and details, but the spirit is the same. And it's well-done.

Wednesday, 10 September 2014

Whimsical creations by Javier Pérez

From facebook.com/artpeople1, deluxebattery.com, thisiscolossal.com, ufunk.net, 123inspiration.com and some other sites.